In “Blake in the Marketplace 1852: Thomas

Butts, Jr. and Other Unknown Nineteenth-Century Blake Collectors,” I examined

the history and significance of an unrecorded auction catalogue that included

23 biblical watercolors and six Paradise

Lost designs of 1808 by William Blake. It has been widely assumed that

these works, sold at Sotheby's on 26 June 1852, once belonged to Blake's first

patron, Thomas Butts. But the vendor, curiously, was Charles Ford of Bath, a

miniature painter. Nine of the watercolors, including three illustrations from Paradise Lost, were acquired by

“Fuller,” and 19, including three from Paradise

Lost, were acquired by Butts Jr. I shared this information with Martin

Butlin, who suspected that I had found the Butts auction that he had been

seeking since 1968 (see his “William Rossetti” 39). He had inferred the

existence of such an auction from William Michael Rossetti, who, in his

catalogue raisonné of Blake's works, identifies Fuller's acquisitions as being

“from Mr. Butts” and quotes descriptions of the works “from the sale-catalogue”

(Rossetti's lists are in Gilchrist's Life

of Blake 2: 199-264). Rossetti's

“sale catalogue” and Butts Jr.'s selling 18 of his 19 works the following year,

on 29 June 1853 at Foster and Son, support Butlin's suspicion: the Blakes in

Ford's auction appeared to have been works that Butts Jr. put up for sale

anonymously but bought in when they

failed to meet their reserve, and not works that he acquired from a third

party.

But I had doubts. Admittedly, the sale

raises the possibility that Butts Jr. owned the Blakes sold because, according

to the catalogue's title page, the auction included a few works by an

“Amateur,” perhaps Butts Jr. But the structure of the auction clearly included

the Blakes among Ford's lots and not the Amateur's, which were tacked on at the

end of the sale. Moreover, why would Butts Jr. buy in 19 of 29 paintings,

two-thirds of what he put up? Did Blake fail to sell in June when he had sold

well at the Foster auction only 12 months later and, more significantly, very

well just three months earlier (with no Blakes bought in), in what was the

first major auction of Blake works, the anonymous sale at Sotheby's on 26-27

March 1852? The vendor of the March

1852 sale has also been assumed to have been Butts Jr., because it too included

Blakes that once belonged to Butts. Hence, by questioning the basic rationale

of attributing Ford's auction to Butts Jr. because it included works once

belonging to Butts, I was also questioning the attribution of the March 1852

sale.

Was it possible that Butts Jr. actually

bought works from Ford that had once belonged to his father but which had left

his father's collection through avenues unknown to us? This, it seemed, was my

primary question, which led in turn to questioning the firmly held assumption

that Thomas Butts Jr., upon the death of his father in 1845, inherited the

Blake collection in its entirety and was solely responsible for its dispersal

at Sotheby's on 26-27 March 1852 and at Foster's on 29 June 1853 (see Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake

p. 336, hereafter referred to as Butlin; numbers are catalogue entries unless

preceded by a “p”). The assumption

seems reasonable, since Butts Jr. was Butts's only living son in 1845, and he

inherited Butts's house on 17 Grafton Street, Fitzroy Square, which presumably

housed the Blake collection. The problem is that the Blakes are not mentioned

in Butts's very detailed 15-page will, nor is there mention of an art

collection or library. The will does mention, however, numerous other

relatives, friends, and houses.

In “Blake in the Marketplace 1852,” by

examining and comparing the three auctions of 1852 and 1853, I cast doubt on

the assumption that Butts Jr. inherited and dispersed all of his father's Blake

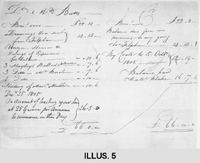

collection. All three auctions contained watercolors matted in a style that I

was able to date and associate exclusively with Butts, which means that the

Blake watercolors in the Ford auction did indeed belong to Butts and not to an

unknown Blake patron collecting at the same time as Butts. With the latter

possibility eliminated, I examined the tastes and behavior of the sales' three

vendors as reflected in their collections and in the number and type of items

bought in. I found that the differences strongly suggested three different

vendors. This approach to the problem yielded a detailed article on, among

other things, Blake's and Butts's different matting styles, Blake's value in

the marketplace in 1852, the provenance of Blake's late Milton designs, and a

few newly discovered Blake collectors. Its major conclusions, though, were that

the vendor of the March and June 1852 auctions was not Butts Jr., but an

unknown Blake collector and Charles Ford, respectively, and that the auctions

were traces of an even earlier dispersal of Blake material by one or more

unknown members of Butts's family.

To support these conclusions, and to

discover who these other members might be and when they might have had access

to—or interest in—the Blake collection, I began researching Butts's genealogy,

particularly his father's family, his own, and his son's. (Each of the three

paterfamilias was named Thomas, who, for clarity's sake, will be referred

to as Mr. Butts, Butts, and Butts Jr. respectively.) I discovered quickly

that

Butts

remains relatively unknown: when and why artist and patron met are unclear,

and the few facts that we do have, such as where he lived while collecting

Blake

and what happened to his collection when he died, are suspect. [1] Moreover,

Butts's family was far more extended and diverse than Blake scholars realize,

and

there were many opportunities for removing Blakes from the

collection without the assistance of Butts Jr.

Discussed here are the two most promising moments, in 1808 and 1845,

when Butts moved to Fitzroy Square and when he died. The former event requires

examining the London residence from which he moved and a residence in Hackney,

one of the “green suburbs” outside of London, which may have been his while

he was collecting Blake. The latter event requires examining Butts's will

and its

arrangements for his second wife, Elizabeth Delauney Butts. [2]

The following information about Butts's

family is based on an examination of various trade, court, and street

directories, Burke's Landed Gentry of

Great Britain (12th edition, 1914), Butts's will, the International

Genealogy Index (IGI), and the rate books, tax records, and baptism, marriage,

and burial registers of the parishes of St. John the Evangelist, Hackney, St.

Luke, Finsbury, St. Leonard, Shoreditch, St. Andrew, Enfield, and a few others. [3] I have also consulted a genealogy of the

Butts's family that was given many years ago to G. E. Bentley, Jr. by R. G.

Robertson, a great grandson of Edward Herrington Butts, who was a disenherited

grandson of Thomas Butts. Bentley kindly showed it to me with the warning that

it is “interesting but not reliable.” The unreliability became quickly evident;

the compiler depended heavily but not exclusively on Burke, which is itself

incomplete, excluded much information that is included in the IGI, while

including information that is not always possible to verify, because it is

either unrecorded in IGI or Burke, or is missing from the other records that

I

have consulted. I refer to this document as the genealogy and mention it only when it varies from Burke.

I

Blake's patron was the child of Thomas

Butts and Hannah Witham. [4] His father, according to the IGI, was

baptized on 14 August 1719 in the parish of St. Dustan, Stepney, as were a

brother Francis and a sister Sarah in 1721 and 1723 respectively. According to

the genealogy, which does not record

his syblings, he worked at the Customs House; according to Burke, he was once

in the Cornet 10th Hussars regiment. He married Hannah on 19 May 1746, in the

parish of St. Andrew by the Wardrobe, London (IGI). The couple's first child

was baptized Thomas on 13 March 1746, in the parish of St. Bartholomew the

Great, London (IGI). This child must have died by the middle of 1756, because

another child, born on 16 June and baptized on 12 July 1756 in the parish of

St. Luke, Old Street, Finsbury, was also named Thomas (parish baptism

register). This son must have died very young, for Blake's patron, the son of

“Thomas Butts, Gent. and Hannah,” was born on 15 December 1759 and baptized in

the same parish on 9 January 1760 (parish baptism register; Burke gives the

date of birth, while the IGI records the date of baptism). Hence, he was not

the same age as Blake (pace Bentley “Thomas Butts” 1052), but two years

younger.

Butts had brothers and sisters. According

to the baptism register of St. Leonard's, Shoreditch, Mr. Butts and Hannah of

Queen Street, Hoglane,” had a son named John (born 7 June and baptized on 17

June 1748). After John's birth, the couple appears to have moved from

Shoreditch to the neighboring parish of St. Luke, Old Street, Finsbury, where,

according to parish's baptism register and the IGI, they had seven children

baptized, including two of the Thomases. Elizabeth was baptized on 14 January 1750,

Samuel on 1 August 1751, Hannah on 1 January 1753, Sarah on 30 January 1754,

and Elizabeth on 21 September 1757. Butts was the last and youngest of the

brood.

Hannah Witham Butts is recorded in the

IGI as having given birth nine times, but apparently only Thomas and Sarah (who

is named in Butts's will and married a William Harris) lived long lives. [5] The

possibility that most of the children died in childhood corresponds with family

lore

as passed down by Ada Briggs, the sister-in-law of Butts's grandson,

Captain Frederick John Butts. She states that Blake's patron and his wife had

many children but most “died young” (93). This is probably not true of Blake's

patron (see below), but it appears to describe the family he was born into,

that of Hannah and Mr. Butts.

According to Burke, Hannah died in 1762;

the genealogy adds that Mr. Butts

remarried and had a son named Thomas, though it fails to record when and whom

he married. I have not been able to confirm the year of Hannah's death in a

burial register (see n5), but the fact that Mr. Butts remarried and had a son

is confirmed by Butts himself. In his will, Butts bequeaths “to each of the

children of my late half sister Mrs. Matilda Floyd (who resided at the time of

her death . . . on the Woolwich Road) who shall be living at the time of my

death the sum of nineteen pounds nineteen shillings and six pence. I give and

bequeath to Mr. Thomas Butts grandson of my deceased father and who is now

Master of the Kentish Town National School and Wardour at the said school house

the sum of three hundred pounds free of legary duty” (will 8). [6] From this passage we can safely infer that

Butts had a half-sister named Matilda and either a brother or, more likely, a

half-brother, whose son Thomas was Butts's nephew and his father's grandson.

The fact that Butts recorded Matilda's children as her children and not his

nephews and neices, and a grandson of Mr. Butts as such instead of as a nephew,

supports the hypothesis that Mr. Thomas Butts was the son of a half-brother.

The IGI strongly supports both

inferences. It records the baptism of a Matilda Butts on 3 January 1776 in the

parish of St. John, Hackney; she was the daughter of a Thomas Butts and an

unnamed woman. The IGI also records the baptism of a John Butts on 9 December

1776 in the same parish; he is recorded as the son of Thomas Butts and an

unnamed woman. The mother of Matilda and John is named Ann in the parish's

baptism register. This John Butts, then, is almost certainly Butts's

half-brother and the person the IGI records as having sired a son named Thomas,

who was baptized on 23 January 1803 in St. Mary Le Bow, London, and who,

presumably, became a school teacher. [7] The Thomas Butts

who sired John and Matilda Butts appears to have been Butts's father, and he

appears to have married

a woman named Ann and to have lived for

a little while in Hackney.

Hackney is an area of London just north

of Shoreditch, with Kingsland Road bordering it on the west. In the eighteenth

century, it belonged to the parish of St. John the Evangelist and, according

to the parish's church and poor rate books, was divided into ten districts:

Church

Street, Mare Street, Well Street, Grove Street, Kingsland, Homerton, Clapton,

Newington, Shacklewell, and Dalston (also spelled Dorleston). Mr. Butts is

recorded in the parish's poor rate books in 1775, but not before, which

corresponds with the births of Matilda and John, and as living in Homerton in

a

house (“late Rowlands”) assessed at £46 (tax collector’s rate book), which was

higher than most of his neighbors. According to the parish's burial register,

he died on 19 April 1778 (Burke gives the date of death as 7 April 1778 but not

the place). The parish's poor rate books reflect his death, in that the 1778

book for the summer quarter listed him as being deficient in payment, and the

book for the first quarter of 1779 listed his house as “empty.

But when did he remarry? The IGI records a marriage, five years after

Hannah Witham died, between a Thomas Butts and an Ann Cook on 16 May 1767 in

the parish of St. Leonard, Shoreditch. According to the marriage license,

Ann Cook

was a “spinster” of the parish of St. Leonard and Thomas Butts was a “widower

of the parish of St. Luke, a description which appears to fit Mr. Butts

exactly. Though the burial registers of the parish of St. Luke are in poor

condition, I have not found an entry for a Butts to suggest that there may have

been another widowed Thomas Butts in the parish. [9]

This couple is recorded in the IGI as

having had five children between 1769 and 1773, at least one of whom was

married in Hackney. According to the IGI, they had a daughter Ann, baptized 29

August 1769 in St. Marylebone, Marylebone Road. In the parish of St. Andrew,

Enfield, the couple had a son named John Timothy, baptized 5 August 1770, a

daughter named Caroline, baptized 25 August 1771, a son named John, baptized 13

September 1772, and a daughter named Lucy, baptized 24 October 1773. According

to the parish's burial register, John Timothy died on 5 October 1770. The

second John would seem to eliminate the possibility that the Thomas Butts and

Ann Cook who lived for a while in Enfield—or at least had children baptized in

that parish—are the same as the Thomas Butts and Ann who lived in Hackney,

since both have sons named John. But the burial register for St. Andrew records

that John died on 13 November 1772. Moreover, Lucy Butts, who was baptized in

Enfield, was married in Hackney. The marriage register for St. John, Hackney,

records her marrying Joseph Wartnaby on 12 September 1798. According to their

marriage license, they were both of the parish, he a “bachelor” and she a

“spinster,” and the witnesses were John Laverner(?) and Thomas Butts.

According to the Hackney rate books for

1786 through 1808, this Thomas Butts lived in Shacklewell and then in Dalston,

where he was Wartnaby's neighbor. Another woman with the surname Butts was also

married in Hackney: Diana Butts, “spinster” of the parish married the

“bachelor” Daniel Fearon of 11 Ely Place, Holborn, on 22 July 1802. She was

probably a daughter of Thomas Butts and Ann Cook, since the witnesses to her

marriage were Lucy and Joseph Wartnaby. The birth of Diana is not recorded in

the IGI. If she was a child of Thomas Butts and Ann Cook, as seems likely, she

might have been mistakenly recorded as "Ann" in the parish register

of St. Marylebone (the source for the IGI entry, where she is recorded as

"Ann," born 4 July 1769). Or she may have been born in 1774-75, after

Lucy, or in 1777-78, after Matilda and John. [10]

Though only one Thomas Butts is recorded

in the rate books, there is another Thomas Butts possibly living at this time

in one of Hackney’s 10 districts. According to the IGI, he married Sarah

Roberts in Ticehurst, Sussex, on 28 March 1785, and they had seven children baptized

in the parish of St. John, Hackney, between 1786 and 1798. According to their

marriage license, she was of the Ticehurst parish and he was of St. Botolph

parish, Bishopsgate Street. There is, however, no apparent connection between

him and Lucy and Diana Butts. Moreover, two men with the same name could be

living in Hackney at the same time but not both be recorded in the rate books.

If living just outside the parish or paying rent inclusive of rates to a

landlord, then his name would not appear in the church or poor rate books. The

parish's book of land tax assessments lists owners and occupiers of properties,

but the latter category often listed "house" or "cottage"

instead of a name. No Thomas Butts is

recorded in the Hackney 1811 census.

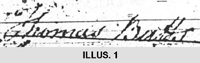

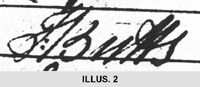

The differences in the signatures on

Lucy Butts’s and Sarah Roberts’s marriage licenses neither prove nor disprove

the hypothesis that the Dalston Butts was Blake’s patron. Though only five letters long, the surname

as signed on Lucy’s  license (illus. 1) and on Sarah’s license (illus. 2)

license (illus. 1) and on Sarah’s license (illus. 2) reveals significant differences in the B,

u, and s. In the former signature,

the Bs stem is slightly curved and

firmly connected to the top loop, which sits on a larger oval to form a 3, the u is round, and the s extends rightward, and both lower case letters are smaller than

the Bs bottom loop. In the latter signature, the Bs stem is sharp and straight, the top

loop is completely free of the stem and forms with its bottom loop an 8 rather

than a 3. The u is formed like a w, cut

very sharp and consists of five distinct strokes instead of three overlapping

ones. The tip of the s shares in the sharp left-to-right

slant as the other letters, and like the u

is larger than the Bs bottom

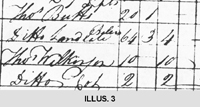

loop. The way the two ts are crossed appears similar, but this

style was quite conventional, as is evinced by the “Butts” and “Ditto” in the

Hackney 1797 tax collector’s record book (illus. 3)

reveals significant differences in the B,

u, and s. In the former signature,

the Bs stem is slightly curved and

firmly connected to the top loop, which sits on a larger oval to form a 3, the u is round, and the s extends rightward, and both lower case letters are smaller than

the Bs bottom loop. In the latter signature, the Bs stem is sharp and straight, the top

loop is completely free of the stem and forms with its bottom loop an 8 rather

than a 3. The u is formed like a w, cut

very sharp and consists of five distinct strokes instead of three overlapping

ones. The tip of the s shares in the sharp left-to-right

slant as the other letters, and like the u

is larger than the Bs bottom

loop. The way the two ts are crossed appears similar, but this

style was quite conventional, as is evinced by the “Butts” and “Ditto” in the

Hackney 1797 tax collector’s record book (illus. 3) and many other such entries

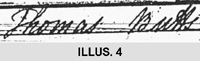

through the rate books. Closer still is

the minister’s hand on Butts’s 1826 marriage license (illus. 4).

and many other such entries

through the rate books. Closer still is

the minister’s hand on Butts’s 1826 marriage license (illus. 4). But on closer inspection, even the crossed ts differ. In the Ticehurst signature (illus. 2), the pen moves half way up

the stem of the second t and curves

over and down in a loop to connect with the s. In the signature on Lucy Butts’s license

(illus.1), the loop begins from the top of the second t and two-thirds down curves under and over through the first t and down the second stem to form

another small loop that goes over to the s. The Ts

in the two signatures also reveal subtle differences. In the Ticehurst signature, the cross bar begins low, with a

large loop that forms an S-like curve and meets and extends the stem; the bar’s

loop rests on the bottom loop, which crosses the stem almost two-thirds

up. The T in the signature on Lucy

Butt’s marriage license is more conventional, with the cross bar, starting from

a tight curl, more horizontal and concave, forming more of an angle with the

stem, while the bottom loop crosses at the midway point.

But on closer inspection, even the crossed ts differ. In the Ticehurst signature (illus. 2), the pen moves half way up

the stem of the second t and curves

over and down in a loop to connect with the s. In the signature on Lucy Butts’s license

(illus.1), the loop begins from the top of the second t and two-thirds down curves under and over through the first t and down the second stem to form

another small loop that goes over to the s. The Ts

in the two signatures also reveal subtle differences. In the Ticehurst signature, the cross bar begins low, with a

large loop that forms an S-like curve and meets and extends the stem; the bar’s

loop rests on the bottom loop, which crosses the stem almost two-thirds

up. The T in the signature on Lucy

Butt’s marriage license is more conventional, with the cross bar, starting from

a tight curl, more horizontal and concave, forming more of an angle with the

stem, while the bottom loop crosses at the midway point.

Of these letters, the B is clearly the most distinct,

different in each hand. The B on Lucy Butts’s license is closest to

the way Butts made his B, and so too

are the u and s. Although no letters from

Butts to Blake are extant, save for the unsigned draft of one sent apparently

in September 1800 (see this article’s epigraph), 28 receipts in Butts’s hand

between 1805 and 1810 are extant. None

has a full signature, all are written in the fine round hand of the

professional clerk, and only one is more than several words long. That exception, though, from December 1805

(Bentley, Blake Records 573-74),

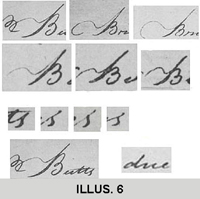

provides a few examples of the letters in question (illus. 5). Butts consistently made his capital Bs in the number 3 style, with a small

top loop connected to a curved stem (illus. 6),

Butts consistently made his capital Bs in the number 3 style, with a small

top loop connected to a curved stem (illus. 6),  and made round us (illus. 6) and ss whose top line hangs far to the right, over the downward stroke

(illus. 6). His ornamental flourish on

the Bs stem is missing in the 1798

signature, but it is also missing in Bs

in other receipts; more troubling is the absence of the straight line that

crosses his double ts and capital Ts whose cross bars are similar but

whose bottom loops do not cross the stem.

If signatures are to play a part as evidence—or if the possibility that

the style of the 1785 signature somehow evolved into that recorded on the 1798

document is to be ruled out—then Thomas Butts’s full signature from 1798 in

letters or documents written in something other than his professional business

hand must be found.

and made round us (illus. 6) and ss whose top line hangs far to the right, over the downward stroke

(illus. 6). His ornamental flourish on

the Bs stem is missing in the 1798

signature, but it is also missing in Bs

in other receipts; more troubling is the absence of the straight line that

crosses his double ts and capital Ts whose cross bars are similar but

whose bottom loops do not cross the stem.

If signatures are to play a part as evidence—or if the possibility that

the style of the 1785 signature somehow evolved into that recorded on the 1798

document is to be ruled out—then Thomas Butts’s full signature from 1798 in

letters or documents written in something other than his professional business

hand must be found.

At this point in my research, it is the

evidence culled from rate books, marriage licenses, and parish registers that

suggests that the Dalston Butts may have been Blake’s patron, for it suggests

that the Enfield Thomas Butts and Ann Cook are the same Thomas Butts and Ann

who lived in Hackney. The presence of a Thomas Butts in Enfield during the

years Mr. Butts is known to have been in Hackney (1775-1778) would indicate

otherwise, but no Butts is listed in the poor rate books for the parish of St.

Andrew for the years 1777-1779, which are the earliest rate books I have been

able to locate for that parish, nor is a Butts listed in the parish's burial

registers after 1772. It appears, then, that Butts's father had started a

second family in 1767, which included Lucy Butts, moved to Enfield by 1770 and

to Hackney by 1775, where he died in 1778. If so, the Thomas Butts who

witnessed Lucy Butts's marriage and was living in Hackney between 1786 and 1808

may have been Blake's patron, who presumably had lived in Hackney with his

father and stepmother by 1775. As we will see, circumstantial evidence,

combined with new information about Mr. Butts, Butts's wife, and Butts's London

residence raises this possibility—or, at the very least, that Butts had a

residence other than 9 Great Marlborough Street while collecting Blake’s works.

The assumption that the Dalston Blake was not Blake’s patron requires numerous

highly improbable coincidences. If,

however, that should be the case, the pursuit, I believe, has been worth the

effort, for it has uncovered a few new facts about Butts and his family while

underscoring how little we know about the man behind so much of Blake’s

artistic production.

II

Butts's mother Hannah Witham died when he

was young, apparently when he was two (1762). He was her youngest child, and he

had at least one older sister who survived childhood. If the “Ann” with whom

his father had two children in Hackney was Ann Cook, then Butts was seven years

old when his father remarried (1767) and was presumably raised by his

stepmother. Ann Cook appears to have given birth seven or eight times, though

only three or four of her children are known to have survived into adulthood.

In this new extended family, Butts may have been the oldest boy, the older

half-brother to Lucy, Matilda, John, and possibly Ann (?Diana). And it appears that when he was around 15

years of age the family lived in Hackney, in the parish of St. John, where

Matilda and John were baptized in 1776 and where his father was buried two

years later.

Butts died relatively well off, but he

appears to have begun his life in more humble circumstances. In 1783, he “entered the office of the

Commissary General of Musters as assistant clerk” (Bentley, “Thomas Butts”

1053). According to Burke, he married Elizabeth Cooper and had three boys,

Joseph Edward, Thomas (i.e., Butts Jr.), and George, born 4 February 1784, 27

September 1788, and 22 September 1792, respectively. [11] The year of his marriage and the parish in

which he was married—traditionally that of the bride—are not recorded in Burke,

the genealogy, or the IGI, nor is the

parish in which his children were baptized. The absence in the IGI indicates

that these events may have occurred in one of over 40 parishes not yet included

in the IGI. On the other hand, their absence may be due to Butts's having been

a nonconformist, as his great granddaughter Mary Butts implies in her memoir, The Crystal Cabinet (164), in which case

there may not be any official or surviving records of his marriage or of the

births and baptisms of his children. [12]

Thomas Butts's familial connection with

Hackney may have extended into his adulthood, possibly as late as 1808. The

Thomas Butts who was Wartnaby's neighbor is first listed in the parish's church

and poor rate books in 1786 in Shacklewell, at number 3 Godfrey Row, where he

paid the taxes on a house assessed at £18 1s.7d.. [13] He moved from there in 1790 to another

dwelling in Shacklewell and from there to Dalston in 1793, where he remained

till 1808. [14] Dalston, the smallest of Hackney's

districts, is at the south-west corner of Hackney and adjacent to the parish

of St. Leonard, Shoreditch. Like Lambeth, it was a village or “green suburb”

on

the outskirts of London. Butts paid the tax on a house assessed at £20; the tax

collector's books list him as the occupier and the Tyson heirs as owner. [15] In 1808, the house was assessed at £40, an

increase suggesting improvements made to the house. The person recorded as

occupying the residence by June of that year, however, is Robert Butts. [16] Who Robert is will be discussed momentarily;

for now we need to recognize that his replacing Thomas in 1808 corresponds

exactly to Butts's move to 17 Grafton Street, Fitzroy Square. Butts is first

recorded at the Fitzroy Square address in Boyle's

Court Directory for 1808. Before that date, the residence was inhabited by

a Mrs. Curtis.

The combined court and commercial

directories published by William Holden support the hypothesis that the Thomas

Butts in Shacklewell and Dalston was Blake's patron. The directories of the

day, such as those published by Kent, Lowndes, and the post office,

alphabetically listed merchants, laborers, professionals et al. at their

business addresses; some commercial directories, such as the Universal Director (1763), also

organized these addresses by occupation to create classified directories, and

others, such as Boyle's General London

Guide (1792), organized them alphabetically and by street. All of them,

however, excluded London's “environs,” i.e., the surrounding villages and

towns. The Holden triennial directories, however, included both commercial

lists and “House-keepers Resident in London, and Ten Miles Circular, in Private

Life.” There was, of course, much overlap between the commercial and private

sections, with merchants and other professionals listing both their business

and private addresses. [18]

In the commercial section of the 1805-07

edition of Holden's and its 1808 supplement we find:

Butts,

Tho, Commissioner of Musters, Whitehall

Butts,

Jn, Gunpowder Office 74 Lombard St

Butts

J, Engineer, Tottenham Str, Fitzroy Sq

Butts

James, Smith, etc. Croydon

Butts,

Mrs. School 9 Great Marlborough St

In the “Private Residence” section of the

same directory and its supplement, we find:

Butts

John, esq 6 Chatham-pl Blackfriars

Butts

John, esq Kensington Terrace

Butts,

Mr. 6 Paragon, Kent Road

Butts

Mr. Tho. Dalston

The Thomas Butts in the commercial

section is, of course, Blake's patron, listed at his office. The second Butts listed is John Butts, who

lived at 6 Chatham-place; he is listed as “Gunpowder Merchant” at both

addresses in the Post Office Annual

Directories for 1804-1809. He

appears to have first entered the London commercial directories in 1797, in Boyle's City Guide, where he is listed

at the Chatham-place address, and the location of his office was first given

in

the 1801 Holden's Supplement of Names

as 1 Savage Gardens. He moved to Lombard street by 1803, where he is listed in

the Kent directories for that and subsequent years till at least 1820. This

John Butts is, I believe, Butts's half-brother John. His profession is

interestingly aligned with that of the Commissary General's Office of Musters,

where Butts made sure that the army's “equipment was in order” (Bentley,

“Thomas Butts” 1053). [19] The third Butts, who is recorded

as “engineer,” is probably

the John Butts of

Kensington Terrace, who is listed earlier in the Universal British Directory (vol. 3) for 1794 in the Kensington

section, under the heading “The following are the principal inhabitants,

Gentry, etc.” There he is listed as “Butts, John, Gent.,” but without a

profession. James Butts is a misspelling of James Butt, as he is listed in

other directories, including the subsequent edition of Holden's. And Mrs. Butts

is Butts's wife, listed at her business address, the address heretofore assumed

to have been the Butts's residence and which, as we will see, was a boarding

school for girls, though it may also have been used as a city apartment for the

Buttses.

In the commercial section, then, there are just four Butts listed. In the private residence section, there are actually only three Butts listed, for the Mr. Butts of Paragon, Kent Road, is a misspelling for Butt, as he is listed in the earlier and subsequent editions of Holden's and earlier editions of Boyle's. These three Butts appear to correspond with the four Butts in the commercial section, that is, they do if the Dalston residence of Mr. Thomas Butts is that of Butts and Mrs. Butts.

“Butts Mr. Thomas, Dalston” is first

listed in the private section of Holden's

Triennial Directory for 1802-04. (Most houses in London's outlying villages

did not have numbers, and most streets were not given names until the

nineteenth century.) The possibility that the Dalston Butts is Blake's patron

is suggested by the relative rarity of the surname (Butt was common, Butts very

much less so, according to private and commercial listings in the directories

and the IGI), and by the company he keeps. The only other Butts listed in the

1802-04 edition are his half-brother John at Chatham-place and the other John

Butts at Kensington Terrace, and no Butts are listed in the commercial section.

The similar manner in which John and Thomas Butts entered the Holden directory

also suggests that the Dalston Butts is Blake's patron. They both enter in the

private section of the 1802-04 edition. They stay in that section in the

1805-07 edition and its 1808 supplement, and add their commercial addresses,

along with Mrs. Butts's, who, as we will see, was listed at this address in an

earlier edition of Holden's and earlier than that in other directories. [20] John Butts, as noted, was also listed in

Boyle's and Kent's directories, and starting in 1803 in the Post Office Annual Directories as well.

Thomas Butts regularly listed his business address in this directory starting

in 1806, after he was dual listed in Holden's, which may explain why he did not

list it in 1809-11 of Holden's. He continued to list his private residence,

however. In Holden's 1809-11 edition, he is listed as “Butts T. Esq. 17 Grafton

st. Fitzroy square,” where he moved in 1808. No other Thomas Butts is listed

at Dalston after this date. For two men with the same name to exit and enter

the

same directory at the same time would be a remarkable coincidence; it seems

more likely that Butts gave Holden's a change of address for the new edition.

Joining him in the private section of the directory's 1809-11 edition were two

other Butts, John of Kensington Terrace and “Butts Rob. Esq., Dalston.”

III

The 9 Great Marlborough Street address,

which is about four miles from Dalston, is much closer to where Butts worked

in Whitehall. This is where Blake sent his letters from Felpham, between

1800 and

1803. [21] Butts is recorded in the Westminister rate

books as paying the taxes on a house “rated at 44 pounds” in 1789. From this,

Bentley reasonably infers that the Buttses lived “in a fine large house” (Blake Records 560 and n1) and that Butts

and Blake may have met in 1789, because the house was just down the street from

Blake, who, between 1785 and 1790, lived at 28 Poland Street. But were Blake and patron really

neighbors—or neighbors who knew one another this early? And did Butts have two

residences?

The first account of Thomas Butts was

written in 1907 by Ada Briggs, whose sister was the second and much younger

wife of Captain Frederick John Butts, the grandson of Thomas Butts and son of

Butts Jr. The article appeared two years after the Captain died, and perhaps

too many years after the events in question for her to have distinguished fact

from family lore. Like Gilchrist (1: 115), she states without proof that Butts

and Blake first met “about the year 1793” (93) and is silent about how and

why. Mary Butts, the Captain's novelist

daughter, suggests in her memoir that her great grandfather “was an early

follower of Swedenborg” (164), raising the possibility that he and Blake met in

1789, the year Blake attended meetings of Swedenborgians hoping to establish a

New Jerusalem Church (Bentley, Blake

Records 34-35). But there is no evidence to prove this association. Unlike the

Blakes', Butts's name does not appear in the register of the 1789 meeting or of

any subsequent meeting.

Given the makeup of his Blake collection,

Butts seems unlikely to have patronized Blake as early as 1789—or 1793. His copies of Visions of the Daughters of Albion, America, Europe, and The Song of Los were acquired from the

Cumberland auction of 1835 and not directly from Blake, and his copy of Songs of Innocence and of Experience was

acquired in 1806 (Bentley, Blake Books

657, 414). Unless Butts's patronage emerged slowly from a friendship with

Blake, it appears likely that the two had met after Blake's most creative

book-making period, 1789-95. The

earliest Blake works traceable to Butts are the biblical temperas (Butlin

379-432), to which Blake appears to be referring in his 1799 letter to

Cumberland: “My Work pleases my employer, & I have an order for Fifty small

Pictures at One Guinea each, which is Something better than mere copying after

another artist” (Keynes, The Letters

11).

The building at 9 Great Marlborough

Street was listed in the 1801 Westminister census as having 22 people, 19 of

whom were female. [22] From this Bentley infers that Mrs. Butts may

have run a boarding school for girls (“Daughters” 116). The inference is

correct, as is evinced by entries for Mrs. Butts in Holden's Triennial Directory for 1805-07 and its 1808

supplement. As noted, she is recorded

under the commercial section but not the private residence section as “Butts

Mrs. School, 9 Great Marlborough Street.”

Her school appears to have been in operation from at least 1790, since

she is recorded in the Universal British

Directory for 1790-92 as “Butts Mrs. 9 Great Marlborough Street.” She is

listed the same way in the 1793 Directory

to the Nobility, Gentry, and Families of Distinction, in The New Patent London Directory for 1795

(a reprint of the Universal British

Directory for 1790-92, and in the Universal

British Directory (vol. 5) for 1798.

Thomas Butts may be paying the taxes on the place, but he is not listed

in any directory that I have examined as living there. [23]

The entry for Mrs. Butts not only

confirms Bentley's suspicions, but it may also explain Blake's choice of

metaphor in his letter to Butts, 22 November 1802. Blake states that he has

“now given two years to the intense study of those parts of the art which

relate to light & shade & colour” and asserts that he understands them

completely, “or Else I am Blind, Stupid, Ignorant and Incapable in two years'

Study to understand those things which a Boarding School Miss can comprehend

in

a fortnight” (Keynes, The Letters

40-41). [24] More significantly, of course, the

identification of 9 Great Marlborough Street as a school indicates that it was

not solely a private residence, which in turn suggests that it might not have

been a family residence at all, or at least not the family's only or primary

residence. The possibility that the location was only a boarding school and not

a family residence is supported by the absence in court directories of a

Westminister address for the Buttses, that is, for Thomas and Mrs. Butts, as

well as the absence of number 9 among the private house residences in Boyle's

street directories in the 1800s (listed are . . . 7, 8, 10, 11 . . .). [25] And, as noted, the baptismal records for

the

Butts children, two of whom (William and George) were born in 1791 and 1792

according to Burke, are not listed in the IGI, and thus the hypothesis that

they were born in Westminister, or that the family belonged to a parish in

Westminister, cannot be proved or disproved at this time.

The 1801 Westminister Census records the

presence of three males, who may have been servants but may also have been

Thomas Butts and his sons Tommy and George, who were 13 and 9 respectively. The

problem here is that Butts’s eldest son, Joseph Edward, born in 1784, was 17

years old at the time of the census and a bit young to be living on his own.

Perhaps Joseph lived primarily in the Dalston residence, or the three sons

lived with their mother and Butts stayed—or for legal reason was listed—in

Dalston. At any rate, the presence of

three males raises the possibility that Butts used the school as a city

apartment and the Dalston residence as a country cottage. The idea that the

Butts family lived in town, at least during the week, is suggested by a letter

of Blake's and an entry in Tommy's diary. On Tuesday 23 September 1800, the day

after arriving in Felpham, Blake writes Butts: “God bless you! I shall wish for

you on Tuesday Evening as usual” (Keynes, The

Letters 24), suggesting that the Blakes and Buttses had met regularly on

Tuesdays, though apparently not always in the evening. Bentley states that one

of these meetings was briefly “recorded by twelve-year-old Tommy Butts in his

diary for Tuesday, May 13th [1800]: 'Mr. and Mrs. Blake and Mr. T. Jones drank

tea with mama'“ (Blake Records 67).

Tommy's diary is untraced, but Briggs quotes two more entries from 1800. On

“September 10th, Mr. and Mrs. Blake, his brother, and Mr. Birch came to tea,”

and on “September 16th, Mr. Blake had breakfast with mama” (96). [26] The latter entry would have been on the

Tuesday before Blake left for Felpham. Where they met is not indicated. They

could have met at Dalston (see n21), but the presence of the 12 year-old with

his mother on a school day and the apparent absence of Butts suggests that they

met at the school, which supports the hypothesis that the school doubled as a

city apartment.

IV

The Commissary of Musters Office closed

as a separate entity in 1818, when it was absorbed into the War Office, and

Butts appears to have retired that year. [27] Years of complaints about the office being

ineffectual and overstaffed had led to an official inquiry in 1812, which

terminated in a recommendation that the office be abolished (Bentley, “Thomas

Butts” 1064). Perhaps the news of such an inquiry or fears of imminent closing

curtailed Butts's Blake acquisitions, c. 1811. The historical record does not

dispute the possible connection: after December 1810, there are no receipts or

documentary evidence to prove that Butts continued his patronage of Blake. [28] Another possible reason for the cessation

of

commissions is the closing of Mrs. Butts's school (see below). Gilchrist states

that Butts eventually “grew cool” to Blake and that he “employed him but little

now, and during the few remaining years of Blake's life they seldom met” (1:

282). The absence of receipts by a professional clerk, whose other receipts

from Blake appear to have been meticulously kept, supports Gilchrist's latter

claim. Blake makes only one reference to Butts after 1811, noting in April of

1826 that Butts had paid him a visit (Erdman 777) and was to receive a proof

copy of the Job engravings (Bentley, Blake

Records 274, 599). They must have also met in September 1821, when Blake

borrowed the Job watercolor illustrations for Linnell to trace, and again in

May 1822, when he borrowed three of the Paradise

Lost designs (Bentley, Blake Records

Supplement 105-06). Though there are no records, Butts must have lent Blake

The Wise and Foolish Virgins and The Vision of Queen Katherine (Butlin

478, 548) as well, because the late versions executed for Thomas Lawrence and

John Linnell (Butlin 479, 549), c. 1822 and c. 1825, are based on tracings from

them. The most one can say, perhaps, is that after 1820 Butts and Blake were

on

good terms but Butts seems not to have been actively adding to his collection

or trying to support Blake financially. [29]

Butts collected the lion's share of his

Blakes between 1799 and 1810. Between 1811 and 1820, contact between the two

men probably never ceased altogether, if, as Bentley argues, Butts had assisted

Blake's brother James in obtaining work as a clerk in “the office of the

Commissary General of Musters in 1814, 1815, and 1816” (“Thomas Butts” 1058).

But there is no hard evidence that Butts commissioned Blake during this time,

the c. 1816 series of Milton illustrations notwithstanding (see Viscomi

“Marketplace” 58 passim).

If Butts maintained a second residence in

Dalston between 1793 and 1808, then the main period of his collecting coincides

with his residency in Dalston. His having had more than one location for

displaying his Blakes, Dalston and Great Marlborough Street, may explain why

there are duplicates in the Butts collection, like the tempera and watercolor

of the Baptism of Christ (Butlin 415,

475) or watercolors of St. Paul and the

Viper (Butlin 509, 510). Perhaps Blake's audience even then was heavily

academic, with Mrs. Butts displaying Blakes in her school as well as in the

Butts's own rooms. Blake finished his biblical watercolors in a style suitable

for display, and they were afterwards matted for display. In this latter style,

the watercolors were trimmed of their wide margins, laid in windows cut out of

large sheets of crayon board, and had inscriptions written on the board below

them in copperplate hand. When this style was first employed is in question,

because the crayon board, which was manufactured by “Turnbull,” could have been

made as early as 1802 or as late as 1819 (Viscomi, “Marketplace” 48 passim). But whatever the date of their rematting,

the watercolors, as received from Blake, were perfectly displayable. They had

wide margins with three or more colored bands framing the image. Works in such “washline mounts” (48) could

be stored in portfolios, but they could also be placed in wooden frames without

front mats. Could the desire to decorate Mrs. Butts's school have motivated the

commission for 50 biblical temperas? Could it have motivated Blake's washline

mounts or Butts's in-laid mounts that were used in the subsequent series of

biblical watercolors?

The hypothesis that the biblical

watercolors may have been painted for the school is worth pursuing, but even if

true it does not mean that the walls and study of the Dalston house were

Blakeless. Countering Butts's reference to his house as a “dung hill,” Blake

described it as a “Green House.” In a

letter of 10 January 1803, Blake states: “But whatever becomes of my labours, I

would rather that they should be preserv'd in your Green House (not, as you mistakenly

call it, dung hill) than in the cold gallery of fashion.—The Sun may yet shine,

& then they will be brought into open air” (Keynes, The Letters 47-48). Through mixed metaphors, Blake complains about

being an ignored artist, about his work having to remain indoors and thus

private during the miserable weather in which he finds himself. But while they

are indoors, in the privacy of Butts's collection, they are safe and

preserved—and are even sure to grow—till he obtains a genuinely appreciative audience

as opposed to the fashionable crowd and exhibition halls of his day. Blake

informs his patron that he prefers his work to remain outside London's

indifferent eye, to be preserved in a living environment rather than to be

shown in a fickle one. Blake's description of Butts's house as “Green,” the

color of living vegetation and the place where vegetation grows indoors all

year long in spite of the weather, appears to have generated the explicit and

even more positive weather metaphors of sun and open air, as well as their

opposition in the adjective “cold,” connoting both the indifference of fashion

and the marble characteristic of the “galleries” of connoisseurs and amateurs,

or as Blake referred to them, “Cunning sures & the Aim at yours” (Erdman

510).

“Green House” suggests the open space of

a free-standing country home or cottage—one with or without extra land—and not

a London row house (see n35). Nor does Butts's description of his house as a

“dung hill” bring to mind a “fine large [London] house.” It does, however,

suggest both country living and his dissatisfaction with it, which perhaps

prompted his move to the more fashionable Fitzroy Square. Blake's description,

on the other hand, supports the hypothesis that the house was located in

Dalston, for it appears to play on Dalston's reputation for having “several

extensive nursery grounds.” [30] At the very least, Blake's description,

combined with the fact that the London residence was a boarding school,

suggests that Butts had a second residence in the early 1800s. By the time he

died, in 1845, he appears to have owned sixteen properties (will), an interest

in real estate that was already present by 1808. [31]

The year Butts moved to Fitzroy Square,

Thomas Butts drops out of the Hackney St. John tax books and his residence is

occupied by Robert Butts, who could be one of two people recorded in the genealogy. The first Robert is listed

as

Butts's third cousin, who was about his age, and the second is listed as a

fourth cousin closer in age to his children. [32] A Robert Butts was listed in Holden's Triennial Directory for

1799-1800 at 16 Field-gate Street, Whitechapel, along with “J. Butts” at 9

Great Marlborough Street. These were the only two Buttses listed. His

profession, like hers (or his, see n23) is listed as “Private.” Robert Butts

is

missing from the directories until Holden's

Triennial Directory for 1809-11, which lists a “Butts Rob. Esq. Dalston.”

As noted, this edition of the directory is the first to list Butts as “Butts

T. Esq. 17, Grafton st. Fitzroy square.” Dalston has no extant poor rate books

for

1810-12, 1815-26, and 1833-42, but the Hackney Census of 1811 lists Robert

Butts in Thomas Butts's house (identified by its proximity to Joseph Wartnaby's

house and place in the record books). The house was inhabited by one male and

two females, presumably a wife and daughter. According to their marriage

license, Robert Butts, “bachelor,” married Mary Hill, “spinster,” both of the

parish of St. John, Hackney, on 1 July 1806; the witnesses were Joseph and Lucy

Butts Wartnaby. [33] Robert and Mary had a daughter named Mary

and a son named Robert, baptized in the parish of St. John, Hackney, on 15

December 1807 and 14 December 1809 (IGI). Presumably, baby Robert died before

the 1811 Census, though I have not been able to find a record of the baby's

death in the burial register for St. John, Hackney. [34]

By 1811, the street was called “Bath

Place,” which was along Dalston Lane, where the present Graham Road

begins. Under “Landholders” in the 1814

rate book, the residence is described as: “Butts Brick ground and Cottage

opposite Cat. and Mutton.” [35] Robert Butts is listed in the 1828 rate

books, still next to Wartnaby, whose house is recorded as “empty”; the location

is now called Graham Place (probably the origin of the present Graham Road),

probably because, as indicated in the 1831 “Plan of the Parish of St. John at

Hackney” (illus. 7), the

land was adjacent to land once belonging to Baron Graham. Robert Butts is still

listed at Graham Place in the 1832 rate books, but

is listed as being in “Kingsland Ward Dalston.” [36]

the

land was adjacent to land once belonging to Baron Graham. Robert Butts is still

listed at Graham Place in the 1832 rate books, but

is listed as being in “Kingsland Ward Dalston.” [36]

Robert Butts is probably the same person

listed in the London Post Office

Directory for 1835 to 1842 as an auctioneer, appraiser, and house agent,

with an office at “Church Street, Hackney,” the name of the north end of what

is now Mare Street. At least for three years (1835-38) his business was listed

as Butts & Owen; according to the genealogy,

Butts had third cousins named Owen, who were Robert's first cousins or first

cousins once removed. [37] After 1843, he is no longer listed in the

LPOD or any of the other directories. [38] If the

Dalston Robert is the person listed in Holden's 1799 directory, married in

Hackney

in 1806, as well as the appraiser and auctioneer (no other Robert

is listed in the directories), then he would have been born c. 1780, about

20

years younger than Butts and eight years older than Thomas Butts, Jr.

Butts was 48 years old when he moved to

Fitzroy Square in 1808, the last year that Mrs. Butts listed in the

directories. While the school might have been vacated, the Dalston residence

was not. If the Dalston residence was Butts's “Green House,” then it follows

that the house almost certainly displayed or “preserv'd” works by Blake. And

since the house was inhabited immediately after Butts by a member of his

extended family, the question of how much of the Blake collection Butts moved

to Fitzroy Square must be asked. If in the Dalston residence some of the

watercolors were displayed, as the original and subsequent matting styles

encouraged, and not stored in portfolios, then possibly some of the

collection-as-furniture remained in Dalston, and quite possibly remained in

Robert Butts's or his descendant's possession, not a difficult thing to imagine

if Robert was an “Appraiser” of art.

V

The idea that the Blake watercolors might

have been furniture is not as demeaning as it sounds. As noted, the works were

finished and then mounted in styles that encouraged display. More important,

“furniture” is apparently how Blake's art works are referred to in Butts's

will. Butts makes no mention of an art collection, let alone a Blake

collection, but he mentions the house in which the collection was kept and gave

it to Butts Jr., along with all its “fixtures and furniture.” [39] Butts

bequeathed to his son the “leasehold dwellinghouse situate No 17 Grafton Street

Fitzroy Square and my Coach house and stable in Grafton Mews in the

parish of Saint Pancras in the County of Middlesex with their respective

appurtenances and also my leasehold dwellinghouse with the appurtenances

situate No 5 Upper Fitzroy Street Fitzroy Square aforesaid wherein my said son

now resides, together with all the fixtures and furniture therein which belong

to me” (will, 6). Seymour Kirkup, a

childhood school friend of Thomas Butts Jr. and frequent guest at his parent's

Fitzroy house between 1810 to 1816, records that he “neglected sadly the

opportunities the Buttses threw in [his] way” to study Blake, adding, though,

that “They (Butts) did not seem to value him as we do now” (Bentley, Blake Records 220n2).

The categorization of Blake's paintings

as furniture and the move to Fitzroy Square from both Dalston and Great

Marlborough Street in 1808 create the first potential rupture in the Blake

collection's line of descent from Butts to Butts Jr. As noted, it seems

possible that a few Blakes from this collection remained in the Dalston house

after 1808 and/or were purchased by Robert Butts. If so, is it possible that the works left behind or purchased are

those that sold at Sotheby's on 26-27 March 1852, whose anonymous vendor is, I

believe, mistakenly assumed to have been Butts Jr., or on 26 June 1852, as part

of Charles Ford's auction?

Of these two sales, the latter is more

likely, because all 29 of the Blake watercolors in the Ford auction were

executed by or in 1808. The 23 biblical watercolors and six Paradise Lost designs are in the same

medium and period, about the same size, and were probably all uniformly matted

(see “Marketplace 1852”). The technical, thematic, and historical coherence of

these 29 works strongly suggests that Ford acquired the works together, as a

small collection, and not one at a time, which is to say, it seems more likely

that they were once together, pared early on from the larger Butts collection,

rather than randomly chosen from the larger collection by Butts Jr. for the

June 1852 auction. Put another way, if chosen in 1852 by Butts Jr., then it is

fair to ask why these works and not others, why this kind of coherence when the

Butts collection was so technically and historically diverse? And why an even split of the 12 Paradise Lost designs? Ford, of course,

may have acquired the Blake watercolors as a group from someone other than

Robert Butts (two other possible sources are Butts's sons Joseph Edward and

George, who died, according to Burke, in 1827 and 1837; see below), but the

possibility of the group's leaving the collection in 1808 and remaining for

years in Robert Butts's possession cannot be ruled out. Nor can the possibility

that they were sold by the auctioneer Robert Butts, either at his Church Street

office or by private contract.

The 39 Blakes in the March 1852 sale

(including six designs to Milton's “Nativity Ode,” watercolors, engravings,

illustrated books, and illuminated books) were more representative of the Butts

collection as a whole than those sold in the Ford auction. As a group, however,

they could not have exited the Butts collection in 1808 and are not likely to

have any connection with Robert Butts. Seven of the ten illuminated books could

not have been left in Dalston, since America,

Europe, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, and The Song of Los were acquired by a “Butts” (presumably Thomas) in

1835 from the George Cumberland sale at Christie's (Bentley, Blake Books 657), Milton was not finished until c. 1811, The Ghost of Abel was printed in 1822, and the copy of Jerusalem in the sale was posthumous.

In “Marketplace 1852,” I argue that most

of the Blakes in the March 1852 sale came from the Butts collection but that

the vendor of the sale was not Butts Jr. The collection that sold consisted of

over 1500 prints and drawings and was apparently built by a connoisseur whose

tastes do not coincide with what we know of Butts, or what is revealed by his

will, or with the tastes of Butts Jr., as revealed by his June 1853 auctions

and his 1862 will. It seems likely that the collector may already have had a

few works by Blake, such as Night Thoughts,

The Grave, and the Job engravings, the most accessible of

Blake's works and in numerous libraries and art collections of the day. But

from whom could have come the watercolors and illuminated books that were

unquestionably from the Butts collection? The primary candidate is Mrs. Butts,

Butts's second wife.

As a 66-year-old widower, Butts married

Elizabeth Delauney, a 56-year-old widow, on 15 June 1826 in St. Pancras, Old

Church (IGI). [40] They lived at 17 Grafton Street, Fitzroy

Square, from 1826 to 1845, when Butts died. According to Butts's will, she was

required to vacate the premises after three months. Butts began his will by

bequeath[ing] to my beloved wife

Elizabeth Butts the sum of one thousand pounds of lawful money of the United

Kingdom and also all articles of plate jewelry trinkets and furniture whether

useful or ornamental whatsoever which belonged to her at the time of our

marriage or which I may have since presented her with. . . . And I do declare

it to be my will and desire that my said wife shall be allowed to retain

possession of and reside in the house I may occupy at the time of my decease

and to have the use of the furniture and all other things that may be there

therein for three calandar [sic] months from the time of my death and that the

usual establishment be kept up and paid and maintained out of my personal

estate during the said period of three calandar months and that none of such

furniture or other things shall be removed from the said premises until the

expiration of that period without the previous consent of my said wife. (will

1-2)

As noted, the Blakes owned by Butts

appear certainly to have been among the “furniture” and “other things” in his

house. The will raises the possibility that some of these household items,

including watercolors and/or books by Blake, were among the “trinkets and

furniture” that he presented to Mrs. Butts. Perhaps the four illuminated books

and The Grave purchased from the

Cumberland sale of 1835 were just such presents, purchases motivated by his

wife's fancy for these kinds of Blake works. It is interesting to note that the

illuminated books from the Butts collection remained together, selling only in

the March 1852 auction and not in Ford's, Butts Jr.'s, or Captain Butts's

auctions. The idea that they stayed together because Butts gave them to his

wife does not seem unreasonable. He did give her—or she inadvertently

inherited—Blake's poem “The Phoenix to Mrs. Butts,” even though it was probably

addressed to the first Mrs. Butts. The manuscript poem, which resembles a page

from Innocence, passed through her

side of the family, surfacing in 1981 (see Viscomi “Phoenix”).

The will also raises the possibility of Mrs. Butts's taking Blakes and furniture while they were still under her supervision, within the first three months after Butts's death (i.e., the summer of 1845). In other words, the stipulation that nothing was to leave the Grafton residence without Mrs. Butts's permission created a window of opportunity. After that, the house and everything in it became the sole property of Butts Jr. This change of title required that Butts Jr., his wife Mary Ann, and their three children (Frederick John, Aubrey, and Mary Ann Blanch) vacate their house at 5 Upper Fitzroy Street and that Mrs. Butts vacate her house of the past 19 years. Whether she and her stepson, Butts Jr., came to some living arrangement is unknown, but it seems unlikely, since she had two daughters, one living a few doors away.

Mary Ann and Caroline Matilda Delauney

are mentioned in Butts's will as “daughters of his wife” and by their married

names, Mary Ann Long and Caroline M. Baker.

Mary Ann Delauney married Charles Long on 24 November 1827, and Caroline

Matilda Delauney married Henry Baker, an architect, on 24 June 1837. [41] Both

daughters were married in St. Pancras, Old Church. In the 1840s, according

to

the postal directories, the Bakers lived at 25 Grafton Street, a few doors

down from the Buttses. Mrs. Butts apparently moved in with the Bakers; she died

in their residence at 11 Upper Gower Street on 24 December 1851 at the age of

81. [42]

The need to move often motivates the sale

of household goods; Butts Jr.'s 1853 sale at Forster and Son appears to have

been motivated by his “Removal from his Residence” (title page of sale

catalogue). Soon after the death of Thomas Butts in April 1845, Butts Jr. moved

in and Mrs. Butts apparently vacated the house. These events are wrought with

opportunities for Blake material given to or claimed by Mrs. Butts to have

exited the Butts collection. Butts Jr.

may not have minded Mrs. Butts taking “furniture,” “whether ornamental or

useful,” that she had been given or wanted, either out of generosity, to keep

the peace, or to help make room for his furniture. He may not have had strong

emotional or aesthetic ties to the works, which were not, as the 1852 and 1853

auction prices of around one pound per watercolor indicate, financially

lucrative possessions. At any rate, it seems reasonable to suspect that Mrs.

Butts had her own small collection of Blakes when she vacated the Grafton

Street residence and began living with her daughter, Caroline Baker.

The titles of the illustrated books in

the March 1852 auction add to the likelihood that most of the Blakes in that

sale came from Mrs. Butts—and lessen the likelihood that Butts Jr. was the

vendor at that auction. The sale included two copies of Night Thoughts (one was colored), a copy of The Grave, and a copy of the Illustrations

to the Book of Job. If we assume that these works came from the Butts

collection, then we must also assume that Butts collected multiple copies of

them, for copies of Night Thoughts

and The Grave sold at Butts Jr.'s

June 1853 auction (lot 143), and a copy of the Job engravings sold at Captain Butts's 1903 auction.

Duplicates may be characteristic of a

connoisseur—or to a person with more than one residence—but would be very

surprising for a man who does not even mention his art collection in his will.

The duplicate most troubling is The Grave,

because Butts Jr. bought a copy at E. V. Utterson's 5 July 1852 auction for 18

shillings (see “Marketplace” 53 passim). This is the copy I believe he apparently

sold at his June 1853 auction, along with the material he acquired from the

Ford sale. But the assumption that Butts Jr. was the vendor of the March 1852

auction requires us to believe that he had just sold a copy of The Grave in that auction for five

shillings only to buy one a few months later for 18 shillings. If, however,

Butts Jr. was not the vendor of the March sale, then The Grave that sold for five shillings may have been the one Butts

acquired in 1835 from Cumberland and presumably gave to his wife. Butts Jr.

acquired Utterson's copy of The Grave

for 18 shillings because he did not have a copy of his own.

The March 1852 sale had an uncolored copy

and a colored copy of Night Thoughts

(lots 58, 59), but it is doubtful that both came from the Butts collection,

since that would have given Butts at least three copies of this book, because

Butts Jr. sold an uncolored copy in June 1853. [43] It seems more likely that Butts owned two

copies, giving Mrs. Butts the colored copy that sold in the March 1852 sale and

his son the copy he sold the following year. That Butts Jr. had a copy would

explain why he passed up two (presumably monochrome) copies at the Utterson

sale. Utterson was a collector who owned duplicates of many items, but it seems

unlikely that Butts would have acquired two uncolored copies of the same book.

Butts Jr. also passed up copies of The

Book of Ahania and America, the

only two illuminated books in that sale. Perhaps he was outbid (£1 13s. and £2

7s. respectively; see “Marketplace” 54, 66)—or perhaps, as suggested above, he

was interested in Blake's watercolors and not his books.

Butts acquired a proof copy of the Job engravings from Linnell in April

1826 (Bentley, Blake Records 591,

599). This copy was almost certainly the one that stayed in the family, selling

in Captain Butts's 1903 auction as “the superb india proof copy (no. 1),

morocco” (lot 21). The copy that sold in March 1852 was “Choice India Proofs”

(lot 60); it was either a duplicate in the Butts collection, or it was one of

the works that already belonged to the anonymous collector of the March 1852

sale. The latter seems more likely; Butts is not recorded as acquiring two

copies in the Linnell receipts, and the “Amateur” who acquired Butts's Blakes

was apparently devoted to engravings and proofs (see lots 62-88, 187-337 of the

March 1852 sale).

VI

The small collection of Blake’s

illuminated books, illustrated books, and biblical watercolors that sold in the

March 1852 auction came from the Butts collection. Could Butts Jr. have sold

them to the vendor of that auction when he moved in 1845,

taking them either from the Grafton residence or from his own residence at

Upper Fitzroy Street? Possibly, but given Butts’s will, Mrs. Butts seems

unlikely to have left Grafton Street empty-handed when she departed in 1845 for

her daughter's house. She may have sold the collection privately between 1845

and 1851 to an unknown print and drawing connoisseur or dealer. Or, possibly,

the collection was sold by her daughter or son-in-law, who presumably inherited

the Blakes upon Mrs. Butts's death in December 1851. It is interesting to note

that the “Phoenix” manuscript was passed down through her other daughter's

family—and perhaps for that reason never made it to the auction halls.

Nearly all the Blakes that sold at

Charles Ford's Sotheby auction on 26 June 1852 came from the Butts collection.

Butts Jr., however, seems very unlikely to have been behind this sale, since

he

was there as a buyer. If the Dalston

Butts was Blake's patron, then it is possible that the collection of Blake

watercolors, all executed in or before 1808, was formed when Butts left Dalston

for Fitzroy Square in 1808, when the Dalston residence was inhabited by Robert

Butts. [44] On the other hand, Ford may have acquired

his Blakes from one of Butts's other sons, either his eldest Joseph, who died

in

1827, or youngest, George, who died

in Toulouse in 1837 (Burke). [45] This possibility is

raised

by Ford's having acquired exactly half of the 1808 Paradise Lost illustrations, a division

that suggests two brothers sharing the series. Butts Jr. did own six of the

illustrations, and two of the three designs that Linnell borrowed in 1822 (Bentley, 275) were eventually in Ford's

collection, which suggests that the series was still intact in 1822.

There were many other opportunities for

Blakes to have exited Butts's collection before Butts died and by hands other

than Butts Jr. (For a list of Blakes that did exit by private sale at unknown

dates, see “Marketplace” 52-53) Joseph's four children were adults by the time

of their grandfather's death in 1845: Edward Herringham Butts, Henry Wellington

Halse Butts, William George Butts, and Elizabeth Butts, born in 1810, 1813, and

1818 respectively. [46] He also had stepdaughters, Mary Ann and

Caroline Delauney, and possibly a stepson, Cornelius Delaney (see Viscomi,

“Phoenix” 13-14). He had a nephew Thomas, the son of his half-brother John, and

unnamed nephews and nieces, the children of his half-sister Matilda. His sister

Sarah and her husband William Harris lived in a house that Butts owned in Stoke

Newington (will 5) and were bequeathed an annuity of £85, to be paid out of the

rent from another of his properties, “No 7 Argyll place (formerly known as No

39

Argyll Street)” (will 2). The possibility cannot be dismissed of a Cooper,

Delauney, Long, Baker, Harris, Floyd, or other members of the Butts family,

including possibly a Fearon or Wartnaby, having acquired Blakes from Butts's

collection. They, or a son other than Thomas Butts Jr., may have acquired

Blakes as gifts or by sale, before Butts died, and sold them to Ford or to

another party from whom Ford purchased them.

As we can see, Butts's family was larger

than Rossetti and Briggs realized, and the provenance of the collection more

complicated. Yet, with 16 houses and many relatives, and moments like weddings

and births for gift giving, it is surprising that so much of the Butts Blake

collection stayed intact. Perhaps it did so because Blake had little economic

or aesthetic value to other members of the family. But we cannot assume that

Butts's other sons or grandchildren other than Captain Butts were not given

Blakes. We mistakenly make that assumption about Butts Jr.'s daughter, Mary Ann

Blanch, who probably owned at least 13 temperas that Rossetti recorded as

belonging to her brother, Captain Butts, and which appear to have been lost in

a fire (see “Marketplace” 45). If either of Butts's sons who died before him

had owned Blakes, that fact would not necessarily have been known to Rossetti,

who used the 1852 and 1853 sale catalogues and Butts Jr.'s Blake collection as

constituted in January 1863, after Butts Jr.'s death, as his base.

My intention here is to challenge the

assumption that Butts Jr. was behind the 26-27 March and 26 June 1852 auctions

at Sotheby's, and that he alone was responsible for bringing into the “open

air” over 160 works by Blake that had long been “preserved” in his father's

“house,” and thereby almost single-handedly providing the grounds for a

reevaluation of Blake in mid-nineteenth-century England. There were more

collectors interested in Blake and interested earlier than previously

recognized, including E. V. Utterson, Charles Ford, the anonymous vendor of the

March 1852 sale, probably Mrs. Butts, and possibly Robert Butts. The case for

Mrs. Butts seems stronger than that of Robert Butts, which is based primarily

on new information about Butts’s father, 9 Great Marlborough Street, and

circumstantial evidence linking Butts to Hackney. Engaging in such speculation,

though it is sure to be extended, corrected, or proved by biographers and

professional genealogists to be merely “numerous highly improbable

coincidence,” is a necessary first step to clarifying the relation between

patron and artist and eventually locating Butts's “Green House.”

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Signature of Thomas Butts as witness on marriage license of Lucy Butts and Joseph Wartnaby, 12 September 1798.

2. Signature of T. Butts on his and Sarah

Robert’s marriage license, 28 March 1785.

3. Tax collectors rate book, Hackney, 1797.

4. “Thomas Butts” in the hand of the minister

on Thomas Butts’s second marriage, 12 April 1826.

5. Verso of 1805 receipt written in Butts’s and

Blake’s hands, with the former signing “Mr. Butts.”

6. A selection of Bs, s, and us from the 1805 receipt.

7. Map of Dalston, showing Bath Place, detail

from a map of Hackney, 1831.

WORKS

CITED

Atkins. P. J. The Directories of London, 1677-1977. London: Mansell, 1990.

DIRECTORIES

CONSULTED

Andrew's

London Directory.

London: J. Andrews, 1790-92.