In my end is my beginning

-T. S.

Eliot, "East Coker"

The man who never alters his opinion is

like

standing water, & breeds reptiles of

the mind

-William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, plate 19

In The Early Illuminated Books, volume 3 of the recent

Blake Trust series of reproductions, we briefly explained why the genre and

structure of The Marriage of Heaven

and Hell are among the book's "most distinctive, most unsettling

primary features." Depending on how one counts, the Marriage text is divided into thirteen

or more sections or units consisting of one, two, three, and more copper plates

[1], plates with and without

illustrations, with and without titles; some of which are "theological

or philosophical, others proverbial, others variously narrative (myths of

origin, interviews, mock travelogues, conversion stories),” with "few

if any characters or settings in common." Moreover, "time and space

are freely manipulated: the narrator travels to hell and back, hangs over

abysses with an angel, and dines in the approximate present with Isaiah and

Ezekiel, while the order of events and the relation of one narrative space

to another are seldom specified." [2]

Is the book "varied and pregnant fragments"; a mere "scrap-book

of Blake's philosophy"; a "structureless structure" about "as

heterogeneous as one could imagine"? [3]

Or is its structure classifiable in terms of genre, as many scholars have

attempted to show, perceiving it as variously as anatomy, Bible, manifesto,

primer, prophecy, or testament? In The

Early Illuminated Books, we assigned it to a subcategory of Menippean

satire identified with the "Greek prose satirist Lucian of Samosata (c.

A.D. 125-200), whose works such as Dialogues

of the Dead, Voyage to the Lower

World, and The True History

(third edition in English, 1781) exemplify the Lucianic 'News from Hell type'"

(p. 118).

Clearly, the Marriage

is an intellectual satire, and its disjointed structure fits reasonably well

into the Menippean category.

Nevertheless, as I argue here, it would be a mistake to infer from this

fit Blake's original intentions for the Marriage—to

assume that he set out to write a Menippean satire or modeled his book on any

one specific work. In this essay, the

first of a three-part study on the evolution of the Marriage, I argue that the idea of a disjointed, miscellaneous work

entitled The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

emerged only after Blake had written and executed plates 21-24 and planned his

"Bible of Hell," and that the structure of the whole work is in some

measure the result of a production history in which sections were written and

executed at different times.

Narrative

discontinuity alone suggests that textual units were not composed in the order

in which they are now read. But it only suggests and does not prove disjointed production, and it does not provide the

clues necessary to establish the sequence in which the textual units were

composed. Analysis of the text cannot answer basic questions, such as whether

individual units or groups of units committed were committed to copper plates

soon after they were written, or only after the entire manuscript was

completed. For clues and for answers, we need to examine technical features

unique to illuminated printing; the first printing of plates 21-24; the

different lettering styles among the Marriage

plates; and, most important, the manner in which plates 21-24 and the other

plates were supplied from larger sheets of copper. This examination will

demonstrate that the four copper plates carrying the text of pages 21-24—which

constitute a sustained attack on Swedenborg—were quarters cut from the same

sheet of copper, were executed soon after their text was written, and were the

first unit produced. They appear to have been written and printed (at least

once) as an independent (though probably unissued) pamphlet, but became instead

the core of what became the Marriage,

generating twenty of its subsequent twenty-three plates. These plates, also

quarters of larger sheets, can be reconfigured into their original sheets; and

the sheets, once sequenced by their lettering styles, confirm the textual units

as revealed by linguistic codes and identify the larger sections or likely

printing sessions to which the units belong. Material evidence provided by the

bibliographic codes—by which I mean lettering style as well as reconstructed

sheets—establishes the sequence in which the units were most likely written and

executed. [4]

When we read the Marriage

units in this sequence—that is, in a chronology of plate production—we begin to

see visual and verbal connections heretofore obscured, connections that illuminate

Blake's composing process and the creative logic underlying the book's

composition. We can trace the development of key ideas and the relation between

unit composition and book production—or, in Blakean parlance, between invention

and execution. In this hands-on, workshop style of composing, in which poet and

printer could execute plates upon completing autonomous textual units, Blake

could think nonlinearly and behave like an artist: ideas and images of a unit

already executed could direct the subsequent creative process. We begin to see how Blake interacted with

his graphic medium and how such interaction encouraged an ever-evolving (what I

have called "organic") mode of composition. Witnessing the Marriage unfold through its production

enables us to answer basic questions about the Marriage's form and Blake's original and final intentions, as well

as general questions about Blake's mode of composing his texts and books. In

short, it enables us to see more of Blake's mind at work

The second essay in my study of the Marriage substantiates the claim made here that plates 21-24 were

written and executed before the other units, probably as an independent,

anti-Swedenborgian pamphlet. I examine

their thematic, aesthetic, and rhetorical coherence and date Blake's interest

in and disillusionment with Swedenborg, placing the latter within the context

of other critiques most likely known to Blake. I identify the primary

Swedenborgian texts that Blake satirizes and examine the major themes that

figure in and help to generate the subsequent plates and units. The third essay

traces these themes and texts through the remaining textual units in the order

in which the units were produced. It focuses on Blake’s allusions to

printmaking and their connection to Swedenborg, examining in detail the image

and symbolism of the cave. The last essay reveals, in effect, that the Marriage is a series of variations on

basic themes first raised in plates 21-24. [5]

I.

Composition in Illuminated Printing

Blake did

not date or sign the Marriage. Until recently, most scholars dated it circa

1790-93. [6] A set of complex allusions

to

Swedenborg, Blake, and Christ on plate 3 suggests

the beginning date. [7] The "June 5 1793" inscription on Our End is Come, an engraving used as

a

frontispiece in Marriage copy B, one

of the earliest copies printed, suggests the conventional end date. The

three-year gestation, the perfunctory mention of Swedenborg on plates 3 and 19,

and the vociferous attack on plates 21-24 suggest that Blake broke from Swedenborgianism

slowly and cautiously, but this conclusion is mistaken. First, the evidence

that the composition of the Marriage

continued beyond 1790 is very weak (see Early

Illuminated Books, 113-16). The engraved frontispiece, for example, is not

printed on a sheet of paper conjunct with the title page, as thought earlier

(see Bentley, Blake Books, 287 n. 3).

With no documentary evidence to prove otherwise, we should accept Blake's

implied date of 1790, which is implied on plate 3 and, more persuasively,

penned-in on plate 3 of copy F—color printed in circa 1794 (see Early Illuminated Books, 145)—as the

end-date. Second, the autographic nature of relief etching encouraged moving

quickly from text to plate (as I will argue below)—or at the very least did not

present any technical obstacles to composition—making it unlikely that a book

of twenty-seven small plates would have taken three years to produce, a good

deal longer than any of the other books Blake was working on during the same

period. The schedule suggested by Blake's professional commitments also

supports a 1790 date: the years 1789 and 1790, which saw the first illuminated

books, were almost completely void of (known) outside commissions for

engravings, whereas during 1791-92 Blake engrave at least seventy plates for

book publishers. [8]

The hypothesis that the Marriage

was in progress for three or more years—

The suspicion that Blake wrote the units of Marriage out of order is neither new nor surprising. Narrative discontinuity, as noted, suggests as much to the readers of Blake. Logic alone indicates that plates 21-24—which explain the grounds of Blake’s attack on Swedenborg—were probably written before plates 3 and 19, where perfunctory mention of Swedenborg appears to rely on information already provided, compositionally speaking. But even those who have seen in Blake's eclectic texts the mind of the bricoleur, or a reviser and cobbler of fragments, still imagine him pulling the fragments together conventionally. [9] In this view, the narrative's disjointedness is a matter of Blake's drawing on disparate discourses and traditions. When one speaks of Blake writing illuminated texts, even a text as “seemingly ad hoc” as the Marriage, [10] one is hard pressed not to envision him writing and rewriting the entire composition on paper before committing it to copper, because one still imagines Blake working as a poet in the manuscript tradition and using illuminated printing subsequently as a mode of reproduction. It is exceedingly difficult to think outside the letterpress paradigm, to conceive of a mode of printing that did not require a finished text or fair copy before execution began; or of a mode of execution in which aesthetic decisions regarding page designs could have an immediate effect on the text, shaping and directing it. In the letterpress paradigm, one simply assumes that a text is written on paper and then set in type, that is produced and completed before being reproduced, with labor moving determinently—and unidirectionally—from author to compositor. Indeed, authors and compositors were not collaborators, and endings were not set before beginnings. [11]

It is commonplace in Blake studies to assert that

illuminated printing united invention and execution, and to view it as a

reaction against the division of labor characteristic of letterpress printing;

but, this assertion has remained mostly theoretical and contradictory. Not

much thought had been given to how—let alone exactly where in production—invention

and execution intersect, except in the person of Blake himself, as author and

printer. But the same laborer does not necessarily mean undivided labor; the

acts of writing and printing in the creation of an illuminated book were still

perceived as occurring separately. This perception is particularly evident

in

Ruthven Todd's theory of illuminated printing, which attempts to explain how

Blake could have avoided writing directly on plates, that is, backward: he

must have transferred from paper first.

Like many before him and since, Todd assumed that Blake produced his books

on paper before reproducing them in metal; this effected a modeling relation

between text and plate and, furthermore, required fair copies. These are

perfectly reasonable assumptions, given that the illuminated page is a print,

which

by definition reproduces images made in other media, whether visual or verbal.

In fact, only by understanding the reasonableness of Todd's proposal can one

fully appreciate how radically Blake broke with conventional modes of composing

and printing by not transferring texts or images. [12]

Todd's theory presupposed that Blake’s adaption of the

“counterproof,” a method of transferring outlines that preserves the direction

of the original in the print. He

proposed that Blake, instead of rewriting his text in graphite on paper,

rewrote it in an acid-resistant ink on leaves coated in gum arabic (otherwise

the ink would enter the fibers of the paper). He rewrote text clearly and

legibly, exactly as he wished it to appear on plates, on leaves cut

specifically to fit their designated plates—or within the outline of the plates

drawn on the leaves—for the plates of an illuminated book are not uniform in

size or shape. He would then carefully register each leaf or page face down

onto its designated plate, pass leaf and plate through the press, and soak the

pair in water to facilitate the transference of the text—which would then

appear backward (“counterproofed”) on the plate and be left standing in relief

after the plate was etched. . Furthermore, the leaves, taken together, would

have constituted a fair copy, but they would have been destroyed in the process

of transference (this, Todd believed, explained the absence manuscripts for the

illuminated books). [13] Producing the leaves in advance in this

manner necessarily divided the manuscripts into pages that corresponded exactly

to plates. Hence, Blake would have been able to cast off copy—and thus execute

plates in order. And, in advance of production, he would have known which pages

were to be illustrated and the size and position of the illustrations. He would

thus have known ahead the proportion between text and image per page, even if

he had not yet determined the illustrations, and have had general mock-ups of

pages. What is produced in metal would be, as Gilchrist mistakenly assumed, an

"imitation of the original drawing," that is, a "facsimile"

of what had been invented on paper. [14]

Todd’s theory breaks down quickly when examined historically

and technically. Conventional methods

of transferring texts in etching and engraving do not work in relief etching,

which is why Todd imagined Blake radically adapting one. The method he and

Hayer describe, however, is strikingly similar to the one invented in 1798 by

Alois Senefelder (an actor who did not know reverse writing) for use in

lithography. In Blake’s time, moreover, all engravers were trained in reverse

writing. The evidence shows that Blake drew his illustrations on plates

directly, without the assistance of transfers; and when he had sketched an

illustration beforehand, he merely redrew it on the plate to fit. The vignette

of Nebuchadnezzar in the second state of Marriage

plate 24 (see illus. 3) is a case in point: When the plate was first printed,

for Marriage copy K, the vignette had

not yet been drawn on it (illus. 1), which meant that Blake had to mask the

plate's unetched bottom half during printing (see n. 22 below). Only after

printing plate 24, with the three accompanying plates, did Blake decide to

continue designing it, at which point he added the vignette of Nebuchadnezzar

from his Notebook (illus. 2). Because Blake redrew this image freehand on the

plate, the printed image is the reverse of the drawing (illus. 3).

The Notebook drawing has no

indication of text and appears not to have been drawn as part of an

illuminated-page design. It may have been drawn as part of an emblem series

that Blake began circa 1789-90 and thus before the writing and execution of

plates 21-24. In any event, Nebuchadnezzar was not chosen randomly; Swedenborg

points specifically to Nebuchadnezzar's dream in Daniel 2: 44 as foretelling

the New Church as the last and eternal church, a passage reprinted in the Minutes (p. 130) of the first General

Conference, which, as I have noted, was attended by Blake. Whether Swedenborg

reminded Blake of an earlier drawing of his or generated a new one, Blake

continued to invent plate 24 and deepen the meaning of his text by responding

creatively to his own first prints. If, on the other hand, he was merely

reproducing a preexistent design, then plate 24 as first printed would probably

have included its vignette, and/or the vignette in the Notebook would probably

have had text, or some indication of its placement in the design. Instead of

transferring or copying the appearance of a page already designed, Blake

designed his page while executing it,

combining his raw materials—text and image—for the first time on the plate

itself instead of on paper.

To assume, then, that Blake counterproofed texts—which

preserves the direction of the original—while drawing illustrations directly on

the plate—which reverses the original—is to assume not only that he could not

write backward but also that he was completely indifferent to the relation of

text and illustration that he supposedly had designed on paper and was

attempting so fastidiously to reproduce in metal. Rather than complicating the

composing process with anachronisms and contradictions, we should assume that

Blake treated his texts as he did his illustrations. He did not need to prepare

a fair copy for a compositor any more than he needed to prepare a detailed

drawing or page design for himself. He merely needed to rewrite his

texts—however they were first prepared and in whatever condition—legibly

(albeit backward) on the plates, placing word and image at the same time, using

the same brushes and pens, the tools of "the Painter and the Poet" (E

692). Thus, Blake probably never had what he did not need, a fair copy of an

illuminated book, let alone a manuscript divided according to its final form on

plates; he did not know—or need to know—the length of any of his illuminated

books when he began to etch their plates. In the case of Marriage, where the bibligraphical evidence indicates that units

were executed at different times (see below), Blake presumably ended up with an

assortment of texts written at different times, probably on various sizes and

kinds of paper, but never a fair copy of a completed manuscript. As with his

other illuminated books, Blake did not know the number of plates the Marriage would be until after it was

executed.

Blake's technique and tools allowed him to combine the raw

materials of text and image on the plate to produce original page designs, as

opposed to reproducing or facsimilizing preexistent designs. The amount of text

written on a plate, the line breaks, letter size, line spacing, and the size

and place of illustrations were not predetermined by a mock-up of that page;

they were aesthetic decisions made during production, which ensured the

marriage of invention and execution. [15] The technique also allowed Blake to begin

etching plates as soon as he had completed writing a section or chapter—that

is, upon completing an autonomous textual unit, or one that he thought was

auto-nomous at the time—should he want to. This unprecedented interplay between

graphic execution and textual composition is easily seen in the structure of Songs of Innocence, Milton, and Jerusalem.

The first work consists of independent texts whose various lettering styles

indicate various plate-making sessions; the second was printed circa 1811 in

two books but was dated 1804 by Blake and begins with the ambitious prediction

that it will be complete "in 12 Books," indicating that production

began long before the text itself was completed; and the last work, which was

also dated 1804 though not completed until circa 1820, has two sets of plate

numbers etched in the metal, the result of Blake inserting plates and changing

his mind about the book's organization.

Being able to execute and design plates before completing

a manuscript made it technically possible for Blake to think and work outside

the

letterpress paradigm—if not also to conceive of producing a disjointed work

like the Marriage. It made it

possible for a text to progress through production, with sections produced at

different times and out of order. However, if it is credible that plates 21-24

were the first unit of Marriage

written and executed, to describe the production of these plates as “out of

order” seriously confuses the issue, for at the time of production there was

no order to be out of. To assume that an order existed at this time is either

to

think in terms of completed manuscript production or to imagine Blake beginning

the Marriage with only a vague idea

of a disjointed, miscellaneous work of which these plates, numbered 21-24 only

later, were to become part. Besides relegating invention to paper, or the mind,

such assumptions raise numerous problems. Why start here? Did Blake think this

episode would make a good opening for the Marriage,

only to change his mind later? Not likely; the "Note" announcing the

forthcoming "Bible of Hell" at the end of plate 24 functions

rhetorically as a conclusion, exactly as it does in the Marriage as a whole. Announcing a forthcoming work at the end of

a

publication is reasonable if the work carrying the announcement is completed,

but it is very odd for Blake to have included such an announcement here if he

had only vague notion of wanting to compose a miscellaneous book. He would have

had to have had to know not only that this text was a section of something

larger but also that it was the last unit of that still unwritten text. [16]

The "Note" contributes to the Swedenborgian

satire, in that it calls to mind Swedenborg's announcement near the end of True Christian Religion: "Inasmuch

as the Lord cannot manifest himself in Person . . . and yet he foretold that

he

should come, and establish a New Church, which is the New Jerusalem, it

follows, that he will effect this by a Man, who not only can receive the

Doctrines of that Church in his Understanding, but also publish them in

Print." [17] Printing Swedenborg's text was the raison

d'etre of the Theosophical Society, founded in 1783 by Robert Hindmarsh and

other Swedenborgians to promote "the Heavenly Doctrines of the New Jerusalem,

by translating, printing, and publishing the Theological Writings of the

Honourable Emanuel Swedenborg." [18] The Society was itself modeled after the

Manchester Printing Society, which began in 1782 to print and publish

Swedenborg's works in English. The Swedenborgian New Jerusalem Church emerged

in January 1788 from a splinter group of the Theosophical Society led by

Hindmarsh. Publishers, including Blake’s friend Joseph Johnson, typically

announced forthcoming books at the ends of pamphlets, but the Swedenborgian

context suggests that Blake had Hindmarsh in mind. [19]

Blake's "Note" ends in the middle of the plate,

but instead of starting another episode, Blake left the space blank, printed it

in that state, and then added a vignette, creating a second state of the plate

(see below). He is clearly thinking of plates 21-24 as an autonomous unit, but,

as will become clear, it was probably not one of several units he was then

planning to write but rather the unintended model for what he was to write. Blake's

"Note" ends a text that at four plates in length was nonetheless the

second-longest narrative in illuminated printing when it was written in 1790.

The longest was The Book of Thel,

which, as we will see, appears to have consisted only of plates 2-7, with just

five text plates, at that time. At four pages, then, the autonomous text

attacking Swedenborg would not have seemed unusually short for Blake to print

as an independent work. The earliest and only extant independent printing of

plates 21-24, known as Marriage copy

K, strongly supports this hypothesis.

II. Marriage copy K: Pamphlet, Proofs, or

Incomplete Marriage?

Plates

21-24 were printed in black ink on both sides of one conjunct half-sheet with

a

bottom deckled edge. [20] The sheet was folded to form a pamphlet with

the following configuration: 21/22-23/24. These four monochrome prints are not

proofs (a correction to the views we expressed in Early Illuminated Books, 115; and see Viscomi, Blake and the Idea

of the Book, 394 n. 10), despite their ink color and uncolored condition and

the presence of two first-state plates (21, 24). Plates 22 and 23 were printed

together as an inside forme and were carefully registered onto the paper and

aligned to one another by eye. They were printed first, with plates 24 and 21

printed as the outside forme and registered by eye to plates 23 and 22, so that

the lines of text on recto and verso of the leaves roughly align. There would

have been no reason for Blake to take such pains with his printing if he were

merely pulling working proofs—that is, checking to see if the design is

finished or stands sufficiently in relief, or if the printing pressure is

correct—but it is perfectly appropriate for producing illuminated pamphlets and

books.

More revealing still, the borders of all four plates were

carefully wiped of ink so they would not print, a practice Blake followed

almost without exception when printing illuminated books between 1789 and 1795. [21] In preparing intaglio plates for printing,

printers wiped clean the beveled edges to ensure an aesthetically pleasing

platemark (the plate’s embossment into the paper); wiping the borders of relief

plates is an adaptation of this practice—though its effect was the erasure of

the tell-tale signs of graphic reproduction—because relief plates were printed

with less pressure and did not leave pronounced platemarks. This erasure

transforms an otherwise overt imposition of metal onto paper into an image that

looks as if it were drawn by hand on the paper, executed spontaneously like

sketch and autograph. Printing relief plates to appear like manuscript pages

would have been unnecessary if Blake’s intent was merely to proof.

Only one other textual unit in the Marriage was printed with this kind of care and attention—and it

too was produced as a pamphlet. "A Song of Liberty," which consists

of plates 25-27, was independently printed at least twice. These printings are

referred to as Marriage copies L and

M; the latter is untraced but described in a 1918 Christie's catalogue (see

Bentley, Blake Books, 287); the

former is now in the Robert N. Essick Collection (illus. 4). Copy L consists

of

three uncolored impressions that were printed in black ink, with wiped borders,

on a conjunct sheet of laid paper folded in half, forming a four-page pamphlet:

25/26-27. (They are not proofs, but are the only extant illuminated impressions

on laid paper [a correction to our statements in Early Illuminated Books, 115; and Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book, 394 n. 10]). Plates 25 and 26 were

carefully registered recto-verso so that their lines are aligned; facing plates

26 and 27 are equidistant from the paper's top edge and the center fold. Plate

25 is in its first state; plate 27 is in a second (and final) state. [22] Though printed separately at least twice,

"Song" may not have been issued as a pamphlet—or at least, despite

its potential for separate printing and issue, no such copies are extant. The

extant and untraced copies both appear to have passed through John Linnell's

family, which indicates that they remained with Blake until at least 1818, when

he met his young patron (see Bentley, Blake

Books, 301). Yet, while these two copies were apparently not issued, one

cannot infer from the absence of other copies that the “Song” was never issued;

by that logic, the unique copies of The

Book of Los and The Book of Ahania

demostrate that those works were never issued. We can say with reasonable

assurance that whatever his original intentions for the "Song," Blake

attached it to the Marriage. These

three unillustrated pages of twenty numbered statements and "Chorus"

read—and look—like a "coda." As we will see, "Song" was

probably written after the Marriage's

first twenty-four plates, appears to have been generated in part by Marriage's theme of a new age (plate 3),

and is the size of Marriage plates

because it was executed using materials left over from the production of the Marriage.

Copy L consists

of

three uncolored impressions that were printed in black ink, with wiped borders,

on a conjunct sheet of laid paper folded in half, forming a four-page pamphlet:

25/26-27. (They are not proofs, but are the only extant illuminated impressions

on laid paper [a correction to our statements in Early Illuminated Books, 115; and Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book, 394 n. 10]). Plates 25 and 26 were

carefully registered recto-verso so that their lines are aligned; facing plates

26 and 27 are equidistant from the paper's top edge and the center fold. Plate

25 is in its first state; plate 27 is in a second (and final) state. [22] Though printed separately at least twice,

"Song" may not have been issued as a pamphlet—or at least, despite

its potential for separate printing and issue, no such copies are extant. The

extant and untraced copies both appear to have passed through John Linnell's

family, which indicates that they remained with Blake until at least 1818, when

he met his young patron (see Bentley, Blake

Books, 301). Yet, while these two copies were apparently not issued, one

cannot infer from the absence of other copies that the “Song” was never issued;

by that logic, the unique copies of The

Book of Los and The Book of Ahania

demostrate that those works were never issued. We can say with reasonable

assurance that whatever his original intentions for the "Song," Blake

attached it to the Marriage. These

three unillustrated pages of twenty numbered statements and "Chorus"

read—and look—like a "coda." As we will see, "Song" was

probably written after the Marriage's

first twenty-four plates, appears to have been generated in part by Marriage's theme of a new age (plate 3),

and is the size of Marriage plates

because it was executed using materials left over from the production of the Marriage.

Textual and visual features of plates 21-24 also support the

hypothesis that the plates were intended as a pamphlet. The absence of a

catchword on plate 24 implies that Blake did not anticipate subsequent plates;

there is also no catchword on plate 20, suggesting that plates 21-24 were also

composed independently of the preceding textual unit, plates 16-20. The text

is

polemically coherent, with well-defined objectives: to undermine Swedenborg's

credibility and to champion Blake and his positions. The former objective

required Blake to refute the New Church's essential claims that it was

"distinct" from the old and that it was founded on the true or

"internal sense" of Scripture (resolutions 1, 12-15, 17, 29, 32; Minutes 126-29). The latter required

Blake to position himself as authentic visionary and offer his own readings of

the Word. The attack also belongs to a turning point in Swedenborg's English

reputation, when his "news from the spiritual world" was wearily

dismissed by his critics but eagerly awaited by his followers. [24] The awareness by both camps of Swedenborg's

claims that he spoke directly with angels provided the requisite context for

Blake's seemingly unprepared-for first sentence on plate 21: "I have

always found that Angels have the vanity to speak of themselves. . . " (see Viscomi, “Lessons of

Swedenborg”). [25]

The unit is structurally and rhetorically as well as

polemically autonomous. Its three features—statement, "Memorable

Fancy," and "Note"—provide the well-defined beginning, middle,

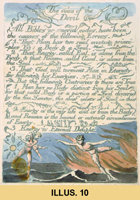

and end of the rhetorically complete pamphlet. The unit begins with an entrance

whose objective is to catch the audience's attention and an exposition that

sets forth the facts, defines the terms, and presents the issues to be proved.

The entrance is beautifully and yet confrontationally realized by Blake's

“divine humanity” (illus. 5); the exposition consists of distinct paragraphs

forcefully explaining why Blake thinks Swedenborg is neither original nor new.

The following section, in which an angel and devil debate the nature of God

functions as the confirmation, in that it sets forth through the two parties

the arguments for and against Swedenborg's idea of God, the central issue

dividing the two visionaries. The devil wins the debate, as is evinced by the

angel's conversion. The text ends with a "Note" that teasingly

promises more infernal readings if the world should "behave well,"

while confidently announcing Blake's future project, whether the world

"will or no." As first written and printed, with Nebuchadnezzar

missing, the "Note" was the entire conclusion; it restates Blake's

basic premise that "infernal" is better than “internal sense”, and

it

leaves the reader wanting—or fearing—more. With the addition of the vignette,

exposition and confirmation are framed by a visual and verbal entrance and

conclusion. [26]

the exposition consists of distinct paragraphs

forcefully explaining why Blake thinks Swedenborg is neither original nor new.

The following section, in which an angel and devil debate the nature of God

functions as the confirmation, in that it sets forth through the two parties

the arguments for and against Swedenborg's idea of God, the central issue

dividing the two visionaries. The devil wins the debate, as is evinced by the

angel's conversion. The text ends with a "Note" that teasingly

promises more infernal readings if the world should "behave well,"

while confidently announcing Blake's future project, whether the world

"will or no." As first written and printed, with Nebuchadnezzar

missing, the "Note" was the entire conclusion; it restates Blake's

basic premise that "infernal" is better than “internal sense”, and

it

leaves the reader wanting—or fearing—more. With the addition of the vignette,

exposition and confirmation are framed by a visual and verbal entrance and

conclusion. [26]

Moreover, the three-part structure of plates 21-24 differs

from other units in the Marriage. In

the other units with these features, the "Note" (on plates 6 and 17)

was placed before the Memorable

Fancies, thereby preventing the unit full closure effected by a Note. And no other unit in the Marriage works as autonomously or, when

finished, returns the reader to its beginning. Plates 21-24 effect this kind

of

closure both thematically and materially. The concluding announcement on plate

24, that "I have also: The Bible of Hell," returns the reader to the

"I" and the resurrected figure on plate 21. When reading the four

plates on a folded, conjugate sheet—that is, as a pamphlet as in Marriage copy K—the reader would return

physically to plate 21 after reading plate 24; flipping to the beginning moves

the reader from defeated tyranny and oppression to the liberated New Man. The

same movement occurs if the pamphlet is opened when one reads plate 24, in

which case plate 21 would be on the right, facing 24 (see illus. 5, 3).

As we can see, the claim that plates 21-24 were the first of Marriage's twenty-seven plates written and executed is certainly plausible; and no technical facts now

known about illuminated printing contradict it. The division of the Marriage plates according to the

formation of the letter g into three

distinct sets significantly strenghtens it.

III. The Letter G and Three Sets of

Marriage Plates

David

Erdman was the first to notice that Blake moved the serif of his gs from the

right to the left. [27] In Blake's first illuminated books, All Religion are One and There is No Natural Religion (both

1788), Blake used a roman script with a right-serifed g; in "The Argument" (plate a3), he also employed the

sans-serifed, italic g that he used

in his manuscripts, including Island

in the Moon (c. 1784) and Tiriel (c.

1789). Blake used the roman right-serifed g

in all but two of the poems in Songs

of Innocence; using the sans-serifed g in

the title of "Night" and the text of "The Voice of the

Ancient Bard." [28] He used the sans-serifed g in all The Book of Thel plates except 1 and 8, which is to say, on plates

2-7, the core of the narrative. (The first and last plates of Thel have long been recognized as

additions to the core narrative [E 790], but I have argued that they were added

sooner than has been supposed; see Viscomi, Blake

and the Idea of the Book, chap. 25, and below). Thel plate 8 has both sans-serifed g and the new left-serifed g;

the sans-serifed g was occasionally

used with a serifed g—right and

left—in the Marriage as well (for

example, plates 21 and 26 [see illus. 5, 4]), but no plate in Thel and only plate 7 of the Marriage has both kinds of serifed g. The leftward g replaced the rightward g

during the production of the Marriage,

and the sans-serifed g dropped out

altogether in the next illuminated books executed, Visions of the Daughters of Albion and America, a Prophecy (both 1793). The right-serifed g reappeared for the major epics, Milton and Jerusalem, begun in 1804, long after all the early illuminated

books were executed.

Why the rightward g

reappeared is not known. The reasons for abandoning it in favor of a leftward g, however, and using the latter

consistently for years, seem easier to determine. Erdman does not propose a

reason, but it seems evident that the change ensured aesthetic consistency in the

script, for the serifs (when present) on other letters, like b, d,

h, l, k, p, and t, lean leftward. They do so because Blake began the letter with a

pen stroke moving to the letter's stem, which is to say, moving in the same

direction that the hand moves while writing (this is true whether writing

forward or backward). A rightward serif on the g, however, requires a backward/downward stroke if the g, like the other letters, was to be

written without lifting the pen; or it required an upward stroke moving in the

direction of the hand but added to the letter last, requiring a two-step

gesture. The leftward serif, then, allowed Blake to start his g at the serif and to write it, like the

other letters, in one continuous act (stroke/serif, top loop, stem, bottom

loop). Once adopted, the new g was

consistently used because it was easier and more efficient to make and, equally

important, its style and execution were continuously reinforced by the style

and execution of the other letters.

Erdman believes that Blake changed his g in early 1791, while working on the Marriage. Consequently,

because Thel plates 1 and 8 have this

new g, he believes that Thel was not finished until 1791 (E

790). Erdman is correct that work on

the two books overlapped (see below), but the overlap probably took place in

1790. As previously argued, the evidence for extending the period of the Marriage's production beyond 1790 is

weak. Erdman also proposes that the Marriage

plates can be divided into sets according to the style of their g; again, he is correct, but he

incorrectly identifies the sets and misinterprets their meaning.

Erdman discerns two sets of plates in the Marriage: plates 2, 3, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13,

21, 22, 23, 24; and plates 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 25, 26,

27 (E 801). But in this scheme, the

plates with the earlier type of g are

not sequential, nor are they the first eleven plates of the book. Why, then,

do

they share the same g? According to

Erdman, "after Blake had a complete version of The Marriage (probably minus the 'Song') on copper, he began

thinking of improvements and amplifications . . . and made them by inserting

new plates, onto which old and new matter were inscribed (at a time when he had

changed his g)." [29] Erdman proposes, in other words, that Blake

completed writing and executing the Marriage

plates before or by early 1791, when he believes that Blake introduced his new g, and that Blake continued to make

changes for the next few years that required making—and thus rewriting—entire

plates. [30] The

plates sharing the early g are from the original “complete

version,” those that were not replaced.

What was on the plates that were replaced is impossible to determine,

because no impressions are extant.

Hence, Erdman can argue that Blake worked on the Marriage for three years—though during most of that time he may

have been merely fine-tuning the text—and at the same time make no attempt to

trace the text’s evolution. Plates with

leftward gs simply replaced plates

whose texts may have been either mostly the same as the replacement’s or

completely different.

Although this hypothesis does not address the issue of plate

chronology, it does subtly suggest that Marriage's

final form was affected by execution, by the remaking of plates—a suggestion

possibly meant to account not only for the change in lettering style but also

for the Marriage's disjointed

structure. Nevertheless, the hypothesis proposes a composing process so

impractical and costly—with Blake replacing over 50 percent of his earlier

work—that it is surely mistaken on economic grounds alone. Mostly, though, it misreads, the

bibliographic evidence because it fails to recognize the flexibility built into

illuminated printing. Blake could execute plates as soon as text became

available. In this light, text with the earlier lettering style reflects the

first parts of the Marriage written

and etched, and text with the latter style reflects portions written and etched

later. Lettering style, combined with narrative integrity, can be used to

identify sets of plates and the textual units within those sets, which is the

first step in tracing the evolution of the Marriage.

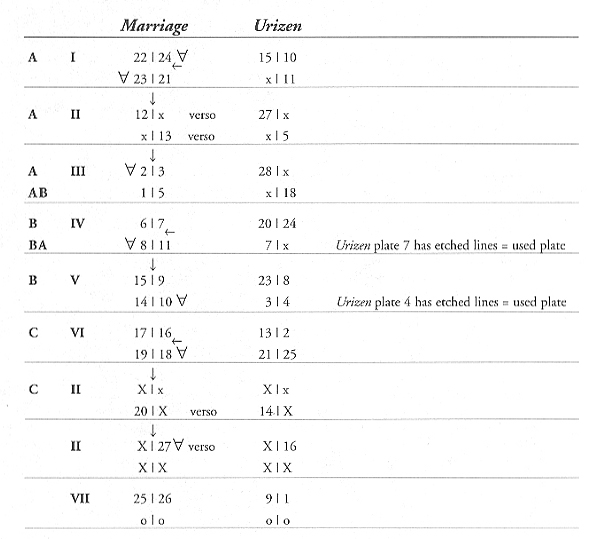

Inspected in this manner, the plates form three sets, instead of two, and can

be sequenced (sets A, B, and C).

Set A consists of plates 2, 3, 11, 12, 13, 21, 22, 23, and

24. Plates 2, 3, and 11 are self-contained units, meaning that their texts do

not carry over to other plates. Plates 12 and 13 constitute "A Memorable

Fancy" as a self-contained unit. Plates 21-24 are an autonomous unit that

includes another Memorable Fancy. Plate 12 has a catchword and this indicates

that its text continues and ends on plate 13; plates 21, 22, and 23 have

catchwords, indicating that they are part of a larger narrative, which ends on

plate 24. Plates 13 and 24 do not have catchwords, nor do plates 2, 3, or 11;

they neither acknowledge nor anticipate subsequent plates—which is to say, the

plates that now follow these may or may not have been produced immediately

after them. The first set of plates, then, appears to consist of five

autonomous units (2; 3; 11; 12-13; 21-24).

Set B consists of plates 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, which form

three interconnected and continuous textual units, with catchwords on all but

the third and last plates. The three sections include "infernal"

readings of Paradise Lost and the Book of Job (plates 5-6), the narrator’s

trip to hell (plates 6-7), and the Proverbs of Hell (plates 7-10). These six

plates form a set that can be sequenced after set A plates: the text carries

over to plate 6 and from plate 7; and plate 7 (illus. 6) has in its first line

the rightward g used on plates 5 and

6—which, however, is immediately followed by the leftward g used on plates 8-10. Plate 7, integral to this group of plates,

is thus a transitional plate, making the entire set transitional as well. [31]

has in its first line

the rightward g used on plates 5 and

6—which, however, is immediately followed by the leftward g used on plates 8-10. Plate 7, integral to this group of plates,

is thus a transitional plate, making the entire set transitional as well. [31]

Set C consists of plates 16, 17, 18, 19, and 20, which, like

plates 21-24, constitute one autonomous unit with "A Memorable Fancy"

written and situated as an integral part of the text. Catchwords are on all but

plate 20. These plates have the leftward g

exclusively and form a narrative unit, including Blake's and the angel's trips

to leviathan's abyss and the cannibalizing monkey house.

Sets A, B, and C are not difficult to identify, and the sets

so constituted indicate that plates 21-24 were among the first Marriage plates written and executed.

But the constitution of the three sets also raises new questions: where do

plates 1, 4, 14, 15, 25, 26, and 27?

Plate 1 is the title plate and has no lowercase g; plates 4, 14, and 15 have the leftward g and are autonomous textual units, although each has some direct

tie to hell and/or the devil (see below). And plates 25-27 also have the

leftward g and form the autonomous

textual unit known as "A Song of Liberty." Were these plates produced

along with the set B or set C plates? After plate 10 but before plate 16? Or

after plate 20? Or were plates 1, 4, 14, and/or 15 produced after plates 25-27?

We can now begin to determine where these plates belong and, more importantly, to

recover the production chronology of all the plates. This may seem like a tall

order indeed, but these objectives are realizable if we examine fully the

bibliographical and technical evidence.

The style

of script provides a material basis for classifying Marriage plates and establishing the roughest kind of production

sequence. The copper on which the script lies provides even more information.

Most illuminated plates were etched on both sides. That

Blake used both sides of his plates can be inferred from the presence of

platemaker's marks, which were stamped into the verso of the sheets, visible in

impressions from Experience, Urizen, Europe, and elsewhere. The versos of the Innocence plates, for example, were used for Experience; the versos of the Marriage

plates were used for Urizen; the

versos of America were used for Europe. The plates that are recto/verso

can be identified by shared measurements (see Bentley, Blake Books, 145, 167, 382, on the likely pairing of plates). In

intaglio graphics, etching the versos of plates still in use was extremely

unusual, because designing, etching, or printing the verso places the recto on

the workbench, brazier, or press bed, where it can be scratched. Scratches on

intaglio plates, like all incised lines, hold ink and thus print as blemishes.

When the design is in relief, however, lines slightly incised across it usually

fill with ink and do not show; if they do show, it is as fine white lines that can

be filled with pen and ink or covered over with watercolors. For aesthetic

reasons, then, etching both sides of an intaglio plate is highly unorthodox,

but these considerations do not apply to relief etchings, and thus Blake could

take full economic advantage of this practice.

Blake also saved money on materials by etching over old

designs—that is, over discarded etchings or engravings—which he presumably

purchased from platemakers at a reduced price. Jerusalem plate 47 (illus. 7) , for example, was drawn and written

over an etching; it is important to note that Blake did not erase the intaglio

line system but simply drew over it, using it as a patterned ground, knowing

that the white lines of the previous design would not interfere with the bold

relief outline and that alterations could be made if necessary when coloring

the impression. And it is equally important to note that he did erase the

incised lines in the area he used for text, a decision probably more practical

than aesthetic, since the text was written with a pen, which requires a

smoother ground than the brush used for the illustration. Removing the

underlying line system makes it easier to write with a pen and easier for the

small letters to be read. Blake did not try to erase the entire design, but

only those areas required by his new page design. The erasure was presumably

done by burnishing the incised lines and then possibly hammering up that area

from the back (a technique called repousage)—assuming

its verso was not to be used. [32]

, for example, was drawn and written

over an etching; it is important to note that Blake did not erase the intaglio

line system but simply drew over it, using it as a patterned ground, knowing

that the white lines of the previous design would not interfere with the bold

relief outline and that alterations could be made if necessary when coloring

the impression. And it is equally important to note that he did erase the

incised lines in the area he used for text, a decision probably more practical

than aesthetic, since the text was written with a pen, which requires a

smoother ground than the brush used for the illustration. Removing the

underlying line system makes it easier to write with a pen and easier for the

small letters to be read. Blake did not try to erase the entire design, but

only those areas required by his new page design. The erasure was presumably

done by burnishing the incised lines and then possibly hammering up that area

from the back (a technique called repousage)—assuming

its verso was not to be used. [32]

Perhaps Blake's most astute economic decision—and presumably

one open to other printmakers as well—was to cut his small plates from larger

sheets of copper himself. The Innocence

plates, for example, are quarters of larger sheets (see Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book, chap.

5). Blake cut plates out of sheets using relatively simple methods, such as

deeply scoring the hand-hammered sheet of copper with a needle and burin and

then snapping it between two plates or boards; or cutting the sheet in half

with a hammer and chisel on an anvil. [33]

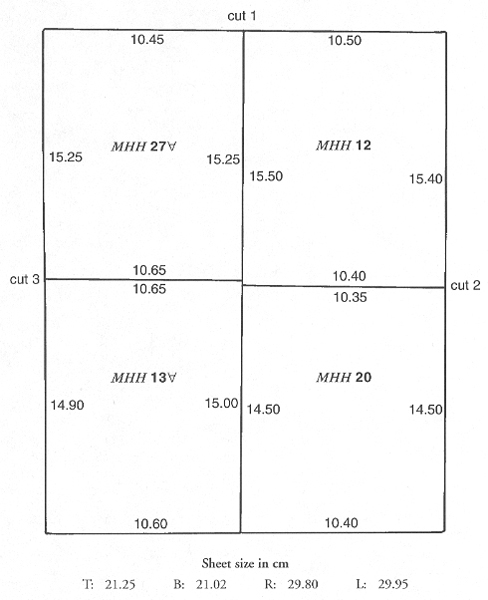

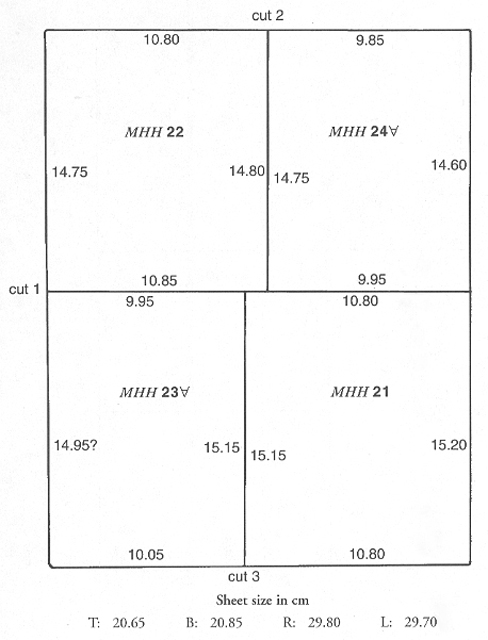

The Marriage

plates are quarters of sheets the size of The

Approach of Doom (approximately 30 by 21 cm). Doom (illus. 8),

in

fact, was quartered, and these were used for Marriage plates 12, 13, 20, and 27. We know this because on the

versos of these plates are The Book of

Urizen plates 27, 5, 14, and 16. The white lines from Doom can still be seen in Urizen

plates 27 (illus. 9) and 14, revealing that the plates are the top- and

bottom-left quarters of Doom

respectively.

When flipped upside down, plate 16 fits neatly into the top-right

quarter, and very faint traces of the earlier design are visible in some

impressions. The only Urizen plate

that fits the bottom right quarter is plate 5, a surprise at first, because

this means that its text was written over relief lines and shallows (the white

areas of the figures' robes). But Doom

was probably etched very shallowly, for nothing more is required of plates

whose relief lines are dense or closely arranged, and, as noted with Jerusalem plate 47, Blake could plane

textured ground to accept text. Moreover, the impression of plate 5 in Urizen copy D shows slight traces of the

earlier design. In the other impressions, these traces are obscured by color

printing and/or washes added to the print. Also, when reconstructed, the

bottom-right corner matches that of Doom;

corners of sheets were usually rounded (from slightly, as here, to markedly,

as

in most of the Job plates) by the

commercial platemaker.

When flipped upside down, plate 16 fits neatly into the top-right

quarter, and very faint traces of the earlier design are visible in some

impressions. The only Urizen plate

that fits the bottom right quarter is plate 5, a surprise at first, because

this means that its text was written over relief lines and shallows (the white

areas of the figures' robes). But Doom

was probably etched very shallowly, for nothing more is required of plates

whose relief lines are dense or closely arranged, and, as noted with Jerusalem plate 47, Blake could plane

textured ground to accept text. Moreover, the impression of plate 5 in Urizen copy D shows slight traces of the

earlier design. In the other impressions, these traces are obscured by color

printing and/or washes added to the print. Also, when reconstructed, the

bottom-right corner matches that of Doom;

corners of sheets were usually rounded (from slightly, as here, to markedly,

as

in most of the Job plates) by the

commercial platemaker.

The quartering of Doom

provides crucial information about how Blake cut his sheets into plates and

about the kind of variants we can expect when trying to reconstruct those

sheets. Doom is recorded as being 29.7 by 21 cm (Bentley, Blake Books, 167 n. 1). These

measurements are close but not exact and actually give the wrong idea of the

plate’s shape. They imply that the sides are the same length and the top and

bottom are the same width, and they hid the slight bowing out across the

plate’s middle. But the plate was not a

perfect rectangle, as the four measurements for Doom reveal: 21.25 cm (top); 21.02 cm (bottom); 29.80 cm (right);

29.95 cm (left). The sheet was first cut in half vertically, and then its two

vertical halves were cut in half (see below, and the appendix, diagram

1). All

four quarters are different sizes and, like the parent sheet, imperfect

rectangles, from which we can infer that the three cut-lines were estimated by

eye rather than measured with a ruler. These variations from perfect rectangles

allow us to reconstruct the parent sheet and determine which quarter was used

for each Marriage plate.

From reconstructing Doom,

we learn that correctly reconfigured quarters form the same shape as the parent

sheet, with a variation of only a few millimeters. The variation in size is minimal,

to be sure, especially given the crude method of cutting sheets into plates and

the loss of metal due to cutting. Variation also exists among impressions

pulled from the same plate. Indeed, plate sizes are inferred from the plate's

slight embossment into paper—that is, from impressions—and impressions from the

same plate may vary slightly in size because different printing papers absorb

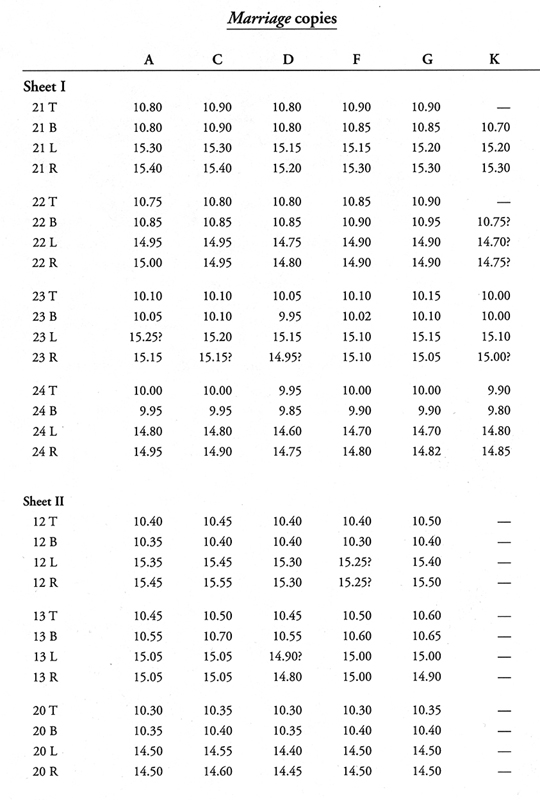

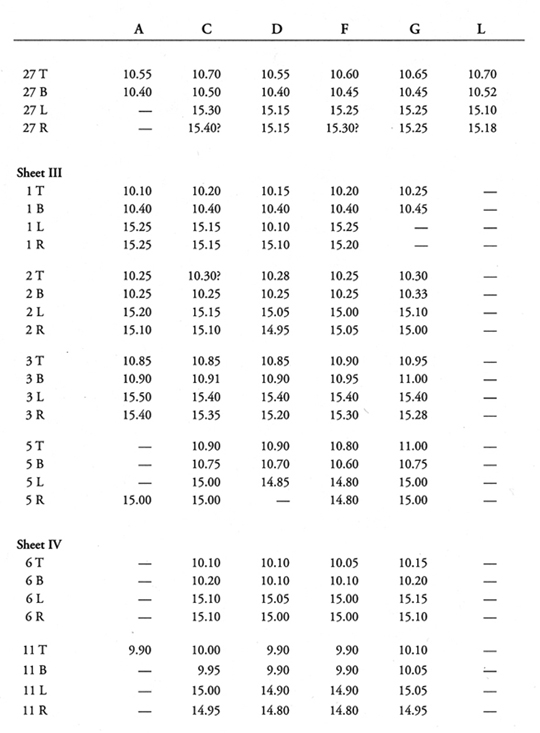

more or less dampness and shrink differently. [34] By measuring the plates of seven copies of

the Marriage and six copies of Urizen, I discovered that plate

measurements could vary from impression to impression as much as 3 mm, but the

shape of the plate (and hence the fit of the quarters) almost always remained

the same because the paper shrank evenly. For example, if the top of the plate

was wider than the bottom, that relation remained, despite variation in the

between different impressions.

We learn from the quartering of Doom that sheets could be cut either vertically to produce two long

halves that were then cut in half, or horizontally into two wide halves that

were then cut in half. The two plates cut from one vertical half will share the same width (bottom and top of the two resulting plates) but rarely the

same length; together, though, they will be the same length (or within 1 mm of

it, depending on the variance of the impressions measured for the

reconstruction) as the combined length of their paired vertical half. Likewise,

the two plates cut from a horizontal

half will share the same length

(right and left margins of the resulting plates) but rarely the same width;

together, though, they will share the same width (or within less than 1 mm) as

the combined width of the sheet's other horizontal half. Because of these

proportional relations, the quarter plates cannot be arranged into sheets

arbitrarily; a plate must share its width or length with another plate, and

then those two plates together must share their combined width or length with

another pair of plates. The reliability, then, that the four plates forming a

sheet are the plates originally cut from that sheet is quite high.

We also learn that sheets of copper Blake started out with

were often irregular, and combined with his method of cutting plates from

sheets and estimating the cut-lines by eye, this irregularity explains why

illuminated plates are slightly uneven—not perfectly rectangular, and never

uniform within a book. Consequently, four measurements must be made to describe

accurately the shape of an illuminated plate. [36] By closely measuring all four sides of the Marriage plates, and noting the shape

and any distinguishing marks in the platemarks—a convex or concave edge, or a

slight nick or swelling inward or outward, or corners that are round, pointed,

dull, or cut—I began to piece together the quarters and reconstruct the

original sheets, much as one would a jigsaw puzzle. [37] Most of Urizen's

plates are on the versos of the Marriage

plates, and knowing the measurements and distinguishing marks of the former

helped me to verify the latter's plate configurations. [38]

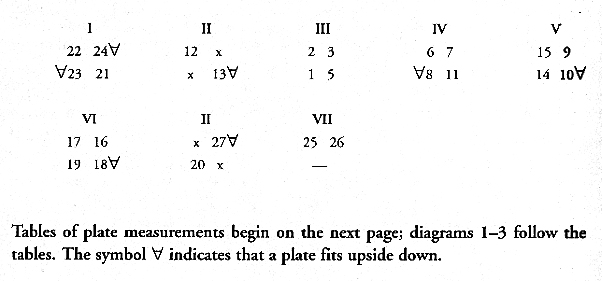

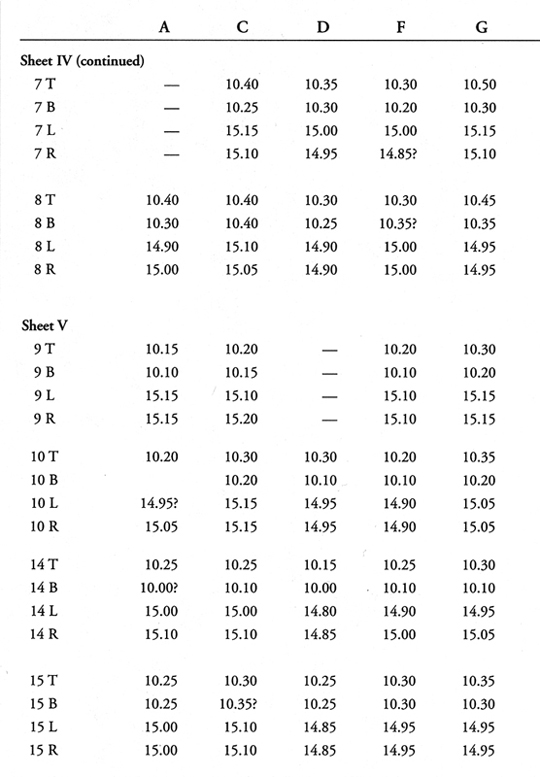

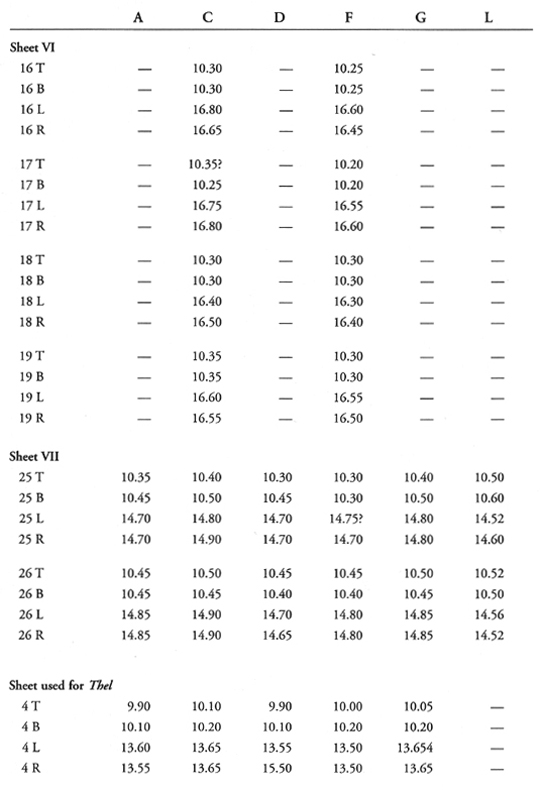

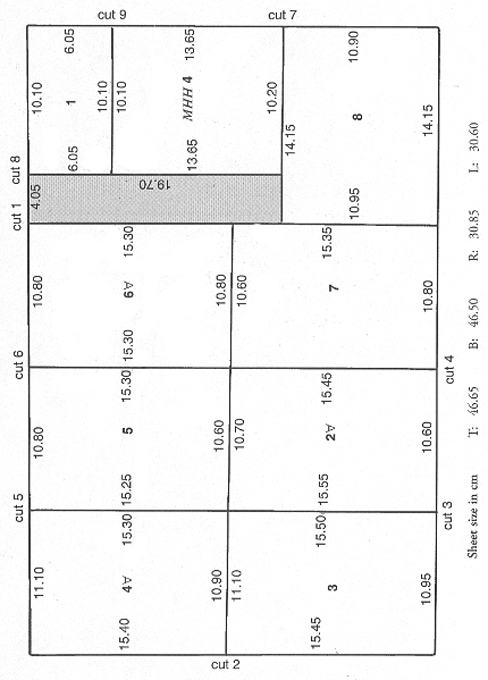

On the next page is a table of reconfigured sheets is based

on minute examination of Marriage

copies A, C, D, E, F, G, and I, and Urizen

copies A, B, C, D, F, and G. In

addition to measuring all four sides of the plates, I also traced in most cases

the right and left margins and used the tracings to find and verify the plate's

pair in the half-sheet and each plate's position in the sheet. (For the

measurements of the Marriage plates,

see the appendix.) The plates are repositioned as quarters: an upside down A next to a plate indicates that plate

fits upside down; an arrow between the vertical or horizontal halves indicates

that sheet was first cut vertically or horizontally, respectively. The second

column shows the probable Urizen

plates that are on the versos of the Marriage

plates reconstructed into sheets. The Marriage

sheets are identified as I-VII and are sequenced according to the A (rightward g), B (rightward g and leftward g), and C

(leftward g) sets discussed earlier.

Small case x refers to a blank

quarter; uppercase X refers to a

quarter that had been already cut and used; lowercase o refers to a quarter whose identity is indeterminate.

From this evidence, we can conclude that Blake used seven

sheets of copper to produce the Marriage.

Had all of them been cut into plates at the same time—as his sheets of paper

were when he printed his illuminated books in small editions—then the resulting

twenty-eight plates, each one a quarter of a sheet,

would

almost certainly have been stored as a group. The plates forming multi-plate units,

such as plates 21-24, or 5-10, or 16-20, would have been chosen from that large

group and would not consistently come from the same or sequential sheets of

copper. But because the plates forming multiplate and contiguous units do

indeed form sheets, the sheets were most likely cut in preparation for those

units—that is, cut as needed rather than cut in advance for a long, let alone

twenty-seven-page, manuscript. That plates 21-24 form one sheet substantially

verifies the hypothesis that these plates were written and executed as an

autonomous unit (see appendix, diagram 2); to support the hypothesis that this

autonomous unit preceded the others as an independent, anti-Swedenborgian

pamphlet, it is necessary to prove that its sheet was the first one cut, which

is the objective of the following section.

In reconstructing the seven sheets, I found just one

anomaly: plate 11 is among the set B plates. I expected to find it cut from

sheet III, which yielded plates 1, 2, and 3—the other set A plates. Instead,

plate 11 was cut from sheet IV, along with plates 6, 7, and 8. It does not

belong to their unit, which contains the Proverbs and their introductory

material, but like plate 6, plate 11 has the right-serifed g, whereas plates 7 and 8 have the left-serifed g. From its place in the sheet sequence,

plate 11 appears to have been executed between plates 6 and 7, after the story

of usurpation and Milton that begins on plate 5 and continues to the middle of

plate 6; but before the Memorable Fancy that starts in the middle of plate 6

and continues with four lines on plate 7—that is, the transitional plate with

both rightward and leftward gs. The

production sequence appears to have been 5-6, 11, 6-10. Are we seeing traces

of a moment of inspiration? Did Blake momentarily stop committing the Proverbs

and

its introductory material to copper to write and execute plate 11? Or had he

brought that text to the printshop along with the texts for plates 1, 2, 3, and

5-10? These nine plates seem to have been executed in the same session (see

below). [39]

V. Sequencing Seven Sheets of Copper

Reconfiguring

the Marriage plates into their seven

original sheets and sequencing them according to their sets A, B, and C

provides a rough idea of the work’s evolution.

Clearly, if we are to understand the genesis of the Marriage in greater detail, we need to sequence the individual set

A plates and determine which of these plates or units was produced first. The

reconfigured sheets suggest four possibilities for the first position: 1)

plates 21-24; 2) plates 12-13; 3) plates 2 and 3; and 4) all or some

combination of these set A plates, produced together. Of these possibilities,

the first is by far the most likely. It is strongly supported by the way in

which the quarters from The Approach of

Doom were and were not used at the beginning of production, and by a

process of elimination that takes bibliographical as well as linguistic codes

into account.

The Approach of Doom (c. 1788), possibly Blake's first

experiment in relief etching (Viscomi, Blake

and the Idea of the Book, chap. 20), predates the Marriage. It was thus on a sheet of copper already on hand when

Blake wrote the set A plates, it is very unlikely to have been the first sheet

cut, because only two set A plates—the textual unit consisting of plates

12-13—were cut from it. This means that two quarters were left untouched at

this time, raising a troubling questions: If Blake cut Doom for the set A plates, why did he not use all four quarters

immediately? If it were cut first, why weren't two of the plates from the unit

21-24, or plates 2 and 3, on those remaining two quarters? These two unused

quarters indicate that Doom was most

likely cut after the sheet yielding plates 21-24; they also indicate that Doom was most likely cut before the

sheet yielding plates 1-3, and 5.

That plate 5 was executed on the fourth quarter of the sheet

that yielded plates 1-3 suggests that these plates were executed near in time;

that the text of plate 5 continues on a plate cut from a new sheet suggests

that Blake knew the text did not end with that one plate but required more.

That this new sheet (IV) yielded plates 6, 7, 8, and 11—plates with both

rightward and leftward gs—and not any

of the plates in the textual units of plates 12-13 and 21-24, indicates that

sheet IV was transitional and that its four plates—and plates 1, 2, 3, and 5

from sheet III and plates 9 and 10 from sheet V—are related and were all

executed after the six plates from sheets I and II.

To assume that Blake began the Marriage with the plates of sheet III (1, 2, 3, and 5) makes no

sense technically, because it also requires assuming that after quartering

sheet III and executing plates 1-3, Blake skipped plate 5 and proceeded to

quarter sheets I and II, whose plates (21-24, 12-13) also have the rightward g of plates 2-3. A plate sequence of

1-3, 21-24, 12-13, 5-10 means a sheet sequence of III, I, II, III, IV, V, which

raises this question: why was the fourth quarter of sheet III used for plate 5

and not for one of the “subsequent” plates, that is, 21-24, or 12-13? Even if we assume that plates 5-6 were not

part of the larger unit as identified here, we are faced with the same

question. For example, if plates 5-6 followed plates 12-13, then why were they

not written on the two remaining quarters from sheet II (Doom)? Why would Blake go

back to sheet III for plate 5 and acquire sheet IV for plate 6? If plates 5-6 followed plates 1-3 for a

plate sequence of 1-3, 5-6, 21-24, 12-13, 7-10 and a sheet sequence of III, IV,

I, II, IV, V, then why weren't the three quarters from sheet IV used for the

subsequent plates?

Blake is highly unlikely to have executed plates 11, 12, and 13 together as one unit, even though plate 11—about "ancient Poets" and their distorted derivative, "Priesthood,"—now introduces the visionary episode about prophets, an episode that exemplifies ideas raised on plate 11. It is unlikely because, as mentioned, plate 11—along with plates 6, 7, and 8, which continue the text begun on plate 5—came from sheet IV; and plates 12 and 13 came from sheet II. Had they been written and executed together, one would expect that plate 11 would have appeared on one of the quarters from sheet II (Doom), or at least on a quarter from a contiguous sheet (e.g., III)—like all other related plates in the Marriage. [40]

There is a logic to using and not using materials, as is

evinced by the pattern of plates that form units also forming sheets. Doom's

unused quarters imply a hiatus in production between sheets II (Doom) and III. The hiatus suggests that

Blake executed the plates of sheets I and II before those of sheet III; and

that when he returned to the studio to execute the next group of plates for

what was now evolving into a book, he brought with him three sheets (III, IV,

and V) and the texts and ideas for plates 1-3 and 5-10—and possibly for plate

11, although this may have been written and produced while Blake was executing

plate 6; and he may have brought plates 14 and 15 as well. Blake either forgot

he had the two Doom quarters or,

because he knew he needed many more plates than two, began using the plates

quartered from the sheets specifically acquired for his new texts. [41] Thus,

the process of elimination yields the same chronology of plate production for

the

set A and B plates that is suggested by the reconfigured sheets of

copper: 21-24, 12-13; 1-3, 5-6, 11, 6-10, followed by plates 14 and 15.

The linguistic code does not falsify this sequence; in fact,

it independently suggests the same. It suggests that plate 3, with its

perfunctory mention of Swedenborg, was written after plates 21-24; and

moreover, that Blake almost certainly did not start with plates 12 and 13.

These plates form "A Memorable Fancy," which retells the narrator's

dinner with Isaiah and Ezekiel. But what is "A Memorable Fancy" and

why is the narrator telling us about this visionary encounter? Three of the

five Memorable Fancies in the Marriage

are on set B and set C plates, which means that they were not yet executed. And

yet the parodic intentions of plates 12-13 seems to require some preparation

or context, nicely provided by plates 21-24, where Swedenborg is attacked by

name;

and his Memorable Relations parodied as "A Memorable Fancy." [42]

The episode on plates 12-13, in which Isaiah states that his

"senses discover'd the infinite in every thing," may have been

inspired by the contrary vision exemplified by Nebuchadnezzar, whose

animal-like posture resembles that of the figure on plate b11 of There is No Natural Religion (see also

the reproduction Nebuchadnezzar, color

plate XVI). Together, the prophets and Nebuchadnezzar—the latter symbolizing

both Swedenborg and the mad King George III—dramatize the theme of plate b11:

"He who sees the infinite in all things sees God He who sees the Ratio

only sees himself only" (E 3). Moreover, Isaiah and Ezekiel, two prophets

whom Swedenborg quotes extensively, are exactly the right witnesses to prove

Blake's claims that Swedenborg's readings of scripture are old and weak and

that his ideas of Christ and the Ten Commandments are ordinary and orthodox

(plates 21-23). Swedenborg says that he, like the prophets, sees angels. He

also claims that

I have been informed how the Lord spoke with the prophets

through whom the Word was given. He did not speak with them as with the

ancients, by an influx into their interiors, but through spirits who were sent

to them, whom He filled with His look, and thus inspired with words which they

dictated to the prophets; so that it was not influx but dictation. And because

the words came forth immediately from the Lord, they are each filled with the

Divine, and contain within an internal sense, which is such that angels of

heaven perceive them in a heavenly and spiritual sense, when men perceive them

in a natural sense.

He

clarifies this in Apocalypse Revealed,

where he states that the prophets distinguished between vision and dictation,

being in the spiritual state for the former and in the body for the latter:

"when they spoke the Word, they were then not in the spirit, but in the

body, and heard from Jehovah Himself, that is, the Lord, the words which they

wrote." [44] Blake's

prophets, however, identify themselves as "poets," affirm an internal

voice, refute external instruction, and make no distinction between vision and

writing, or between spirit and sensual body. In the Marriage, Isaiah says:

I saw no God. nor heard any. in a finite organical

perception: but my senses discover'd the infinite in every thing, and as I was

then perswaded. & remain confirm'd; that the voice of honest indignation is

the voice of God. I cared not for consequences but wrote. (Plate 12)

Isaiah ironically echoes Swedenborg's

description of Adam and the ancients:

So with the man of the Most Ancient church; whatever he saw

with his eyes was heavenly to him; and thus all things and everything with him

were as if living. From this it may be seen what his Divine worship was, that

it was internal and not at all external. [45]

Blake

will advocate a return to this visionary state on plates 3 and 11, with the

return of Adam to Paradise and the mythopoeic perception of the "ancient

Poets."

Writing as "poets" without fear of consequences

contrasts starkly with the "systematic reasoning" of angels (plate

21); the first alternative also alludes to the poet Blake writing this

prophetic prose and to his every other tract, and to Christ, whom the Devil

defines as acting "from impulse; not from rules" (plates 23-24):

behavior characteristic of the artist. The devil’s and angel’s debate over

whether God is internal or external echoes a debate recurring in Swedenborg’s

writings about whether salvation depends on “faith [in Christ] alone, without

the works of the law—which faith is mean by the dragon”—or in Christ as well as

the law (Apocalypse Revealed, n.

539). The debate is reconfigured on plates 12-13, where the connection of art

and Christ is made explicit when the prophets state that "in ages of

imagination this firm perswasion removed mountains." Christ states,

"If ye have faith . . . ye shall say unto this mountain, Remove hence to

yonder place; and it shall remove; and nothing shall be impossible unto

you" (Matthew 17: 20). By appropriating poets, prophets, and Christ for

the devil's party, Blake has further defined the dialectic that unfolds on

plates 21-24 between angels and devils on plates 21-24 in terms of religion and

art. More to the point, he has strengthened the devil's refutation of the

angel's claim that Christ sanctioned the Ten Commandments (plate 23) and

strengthened his own claim that the New Church is anything but "new"

and "distinct" (plate 21-22). Indeed, Blake again implies that

Swedenborg misreads the Word and its prophets and thereby subjects people to

false ideas, exactly like the Church he criticizes. Ezekiel states: "from

[his and Isaiah's] opinions the vulgar came to think that all nations would at

last be subject to the jews . . . [which] is come to pass, for all nations

believe the jews code and worship the jews god, and what greater subjection can

be[?]" (plate 13). The "code" refers to the "law of ten

commandments" advocated by the angel and New Church but "broken"

by Christ (plates 23-24). Swedenborg's worship of this code and God, then,

reveals that he oppresses Christ. What Swedenborg worships confirms Blake's

accusation that despite his showing "the folly of churches &

expos[ing] hypocrites," he still "has written all the old

falshoods" (plates 21-22). By tying Swedenborg to the very

"code" the impulsive Christ rejects, Blake again refutes both of

Swedenborg's claims—that the New Church is distinct from the old and that he

recognizes the true Christ—and again affirms the message of plates 21-24, that

the problem lies not in the Word but how it is read. Is it read diabolically or

systematically, infernally or internally?

Swedenborg's God, if perceived "infernally," is

revealed to be the dominating external God of the "jewish code" and

as such "merely derivative," having, like "all Gods,"

"originate[d] in" "the Poetic Genius" (plates 12-13; see

also All Religions are One plate 9).

While Blake does not mention "poetic genius" and "origin"

on plates 21-24, he implies both. The "poetic genius" is implied

through the hierarchy of writings, with the "sublime" of

"Shakespeare" and "Dante" representing the truly inspired

works of "masters," and Swedenborg's "recapitulations" of

"superficial opinions" representing memory and the perpetuation by

followers of "all the old falshoods." The ideas of origin and originality are implied in Blake's claim

that Swedenborg is a copyist and is so because he fails to consult devils who,

as the origin of Blake's "The Bible of Hell," represent the

"poetic genius." The idea that the "poetic genius" is the

origin or "first principle" of perception and creativity is proposed

on plates 12-13, while creativity's symbolic connection with hell will be made

explicit later, on plate 6, by the narrator's trip to hell, where

"fires" are "the enjoyments of Genius."

Blake started the text of plates 12 and 13 on new plates, as

opposed to starting it on a plate as

a continuation of the preceding and contextualizing text or narrative; the

Memorable Fancies on plates 22, 6, and 17 begin midplate. This is consistent

with the hypothesis that plates 12-13 were written and executed independently

of the plates and narratives that now precede them, and were composed in light

of a previously executed text that now follows them. As an autonomous textual

unit, plates 12-13 seem to develop or extend contraries and themes propounded

in plates 21-24, including originality and imitation, impulse and law,

inspiration and memory, liberation and subjection, reading and misreading. The

thematic relation between plates 21-24 and plates 12-13 places the former unit

first, verifying the bibliographic code and significantly strengthening the

hypothesis that plates 21-24 were not only executed first but also originally

intended as an anti-Swedenborgian pamphlet. It seems reasonable to speculate