Digital Facsimiles:

Reading the William Blake Archive

Joseph Viscomi

Tyger,

Tyger, burning bright,

In

the forest of the night:

What

immortal hand or eye,

Could

frame thy fearful symmetry?

(1-4)

I.

The Case for Facsimile Reproduction

The

lines of the epigraph are from the most anthologized poem in English

literature. [2] They are, of course,

the first four lines

from William Blake’s “The

Tyger,” one of twenty-six poems in his Songs of Experience, first printed in 1794 with twenty-one

poems and combined at that time with his Songs of Innocence of 1789 to create his best known

illuminated book, Songs of Innocence and of Experience. These bibliographical details, though, only hint at

the complexities of studying and editing Blake’s poetry, complexities

revealed more quickly and clearly by a simple comparison between the lines as

they appear above and the form in which they were originally read (illus. 1).

appear above and the form in which they were originally read (illus. 1).

Immediately, we see that Blake’s text is calligraphic, illustrated,

and finished in watercolors, features which textual scholars have argued

theoretically—and,

I believe, we sense intuitively—as contributing to the meaning of the

whole. [3] Indeed, we recognize the typographic translation

as grossly

distorting the original artifact, a hand-colored

impression printed from a copper plate executed in “illuminated printing”

(i.e., “relief etching”), a technique Blake invented in 1788.

Instead of the needles, burins, and other metal tools of the graphic artist,

Blake worked on copper plates with pens, small brushes, and an ink impervious

to acid (probably asphaltum in turpentine mixed with a little lampblack);

he wrote text backward, illustrated it, and etched the untouched metal below

the surface to leave the integrated design in printable relief. Working

on

metal with the tools of poet and painter enabled Blake to create a multi-media

space, a “site” where poetry, painting, and printmaking came

together in ways both original and characteristic of Romanticism’s

fascination with autographic gesture, with spontaneity, intimacy, and organicism.

Blake used illuminated printing as a mode of production rather than

reproduction, combining text and illustration on the plate for the first time

rather than reproducing a pre-existent page design. The etched design, however,

is continually recreated when printed, for it is printed in different inks

and colored differently at different periods. The result is a “printed

manuscript,” an oxymoron coined by Robert Essick to describe Blake’s

ability to produce repeatable yet unique works.  For example, “The Tyger”

above (illus. 1) is from an early copy of Songs designated

as copy “C”; its Experience impressions were printed in 1794 in yellow

ochre ink on both sides of fine wove paper (which when bound with other leaves

created facing pages) and finished in light watercolor washes. This version

looks and feels quite different from the impression in late copy Z

(illus. 2), which was printed in 1826 in orange-red ink

on one side of the leaf, elaborately colored, strengthened in pen and ink,

and given frame lines like a miniature painting.

Now, add to this basic comparison numerous other impressions produced

from the same plate at different times and in different production styles,

each looking slightly to dramatically different from the other, each with

the possibility of textual variants, and nearly all occupying a different

place in each copy of the book, and you will begin to glimpse the bibliographical

and textual difficulties confronting the editor—and student—of

Blake.

For example, “The Tyger”

above (illus. 1) is from an early copy of Songs designated

as copy “C”; its Experience impressions were printed in 1794 in yellow

ochre ink on both sides of fine wove paper (which when bound with other leaves

created facing pages) and finished in light watercolor washes. This version

looks and feels quite different from the impression in late copy Z

(illus. 2), which was printed in 1826 in orange-red ink

on one side of the leaf, elaborately colored, strengthened in pen and ink,

and given frame lines like a miniature painting.

Now, add to this basic comparison numerous other impressions produced

from the same plate at different times and in different production styles,

each looking slightly to dramatically different from the other, each with

the possibility of textual variants, and nearly all occupying a different

place in each copy of the book, and you will begin to glimpse the bibliographical

and textual difficulties confronting the editor—and student—of

Blake.

How

editors resolve these difficulties affects directly how Blake is known and, of

course, what Blake we come to know. Typographic transcriptions, which abstract

texts from the artifacts in which they are versioned and embodied, made good

economic but poor editorial sense. They made possible inexpensive editions of

Blake’s poetry and his inclusion in anthologies—and thus

classrooms—but, as we see, at the expense of Blake’s intentions.

Such transcriptions are “reader’s texts” when Blake’s

idiosyncratic punctuation is corrected, with stops determined by modern rules

of syntax or grammar. For example,

Keynes edits the lines as:

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forest of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

(1-4)

Erdman,

on the other hand, attempts to reflect Blake’s markings as closely as

type allows (many of Blake’s marks have no typographic equivalent), choosing

marks by consensus, by comparing numerous printings of the text to see which

mark—e.g. comma or period—is most often present:

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forest of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

(1-4) [5]

The

resulting composite text may claim to have excavated the text as executed on

the copper plates, but it no more corresponds to an actual printed work than

the user friendly reader’s text.

Relative to type, unscaled monochromatic reproductions of colored

illuminated pages move readers closer to Blake’s vision, though they

fail to capture size, color, and texture of the original.

At the other end of the reproductive continuum are facsimiles, and

the finest of these, like the hand-colored collotypes produced by the William

Blake Trust between 1952 and 1978, represent the originals more successfully,

but as expensive limited editions they are themselves not readily available

to students. And even they fail to provide the kinds of detail necessary

for good art historical and editorial analyses. To discern, for example,

whether

a mark was etched on the copper or added or changed afterwards in printing

or coloring the impression would still require close first-hand scrutiny

of

the original works, which are housed in international collections at widely

separated locations. Moreover, facsimiles and reproductions both present

an

edited Blake, edited in the sense of works selected for reproduction and

in the way images are reproduced. Indeed, the public’s exposure to

Blake—and

this includes many advanced students and not a few scholars—has been

narrowly restricted to a small number of items that have been too frequently

reproduced. [6] For example, Songs

copy Z (illus. 2) is one of only two copies (both late)

commercially reproduced in color, whereas the less flashy early copy C (illus.

1) has never been reproduced. Reproductions and facsimiles also edit

Blake by reproducing only the image and not the full sheet, which means

bibliographical

information, such as paper’s size and the plate’s registration

to the paper, goes unrecorded and Blake—or Mrs. Blake—appears

to be a neater printer than he/she was and the pages visually more uniform

than they are.

Typographic editions and reproductions of only about 20% of Blake’s

illuminated canon (40 or so of the 175 copies of the 19 illuminated books

Blake produced between 1788 and 1827, when he died), reproduced sometimes

well, sometimes execrably, but in no coherent historical order and insufficient

detail to sustain scholarly and editorial research—this was the state

of Blake studies when in 1993 the editors of the Blake Archive began to

conceive

of reproducing Blake digitally. Morris Eaves, Robert Essick, and I had just

finished editing nine illuminated works for the Blake Trust and, while pleased

with the scholarly apparatus we developed, we were frustrated by the relatively

small number of reproductions we were allowed. With the economic restraints

of the codex form fresh in mind, we visited the Institute for Advanced Technology

in the Humanities at the University of Virginia, where we began to envision

a critical hypertext of approximately 3000 images, 2/3rds drawn from the

illuminated works and the remainder from Blake’s paintings, drawings,

prints, and manuscripts, with all texts and images deeply encoded in SGML.

We would represent

the illuminated canon by exemplary copies from each printing of each illuminated

book, as well as copies from the same printing session with important variants

in coloring, motifs, arrangements, etc., along with related material, such

as drawings, proofs, and sketches, so that the production history of each

book would be recorded. [7] About half of the books selected for

inclusion had never been reproduced before—including six of our eight

copies of

Songs. Our typographic

transcriptions of texts would be, in the terms of textual criticism, as "diplomatic"

as the medium allows. That is, in line with the archival dimension

of our project, our texts are conservative transpositions of the original

into conventional type fonts, retaining not only Blake's capitalization,

punctuation (within the limitations of typography), and spelling, but also

(for the first

time in a complete edition) his page layout.

Unlike printed editions of Blake, which, as noted, have typically

chosen among the textual features of various copies to produce a single

printed text,

the texts in the Archive are specific to individual plates;

each transcription

is of a particular plate in a particular copy and no other. [8]

Once

archived digitally, structured and tagged (indexed for retrieval in SGML,

adapted to the purpose), annotated with detailed descriptions, and orchestrated

with a powerful search engine (in this case DynaWeb software), the images in the Archive could be examined like

ordinary color reproductions. But

they could also be searched alongside the texts, enlarged, computer enhanced,

juxtaposed in numerous combinations, and otherwise manipulated to investigate

features (such as the etched basis of the designs and texts) that have

heretofore been imperceptible without close examination of the original works.

Even scholars who are able to globetrot from collection to collection end up

relying heavily upon their inadequate memories, notes, photocopies, and

photographs to compensate for the distances in time and space between

collections. Seeing the original

prints, paintings, manuscripts, and typographical works is good in itself; but

seeing them in fine, trustworthy reproductions, in context and in relation to

one another is the scholarly ideal.

Difficulty of access to originals and reliance on inadequate

reproductions has handicapped and distorted even the best efforts. Again, the result has all too

frequently been distortions of the record, misconstructions, and the waste of

considerable scholarly labor.

In

the broadest terms, the Blake Archive is a contemporary response to the needs

of a dispersed and various audience of readers and viewers and to the

corresponding needs of the collections where Blake’s original works are

currently held. Both the audience

and the collections, institutions, and curators on which it depends share a

strong interest in the accessibility and the preservation of Blake’s

works. The Blake Archive attempts

to serve both sets of needs at once by providing free access to its Web site,

where access to Blake’s works is possible to a degree heretofore

impossible. But we have designed the site primarily with scholars in mind. For them we believe that the Archive

will soon become not merely useful but indispensable—as a handy

reference, a point of departure, or a site of sustained research—because

of the fidelity of our reproductions. Reproductions can never be perfect, and

our images are not intended to be “archival” in the sense sometimes

intended—virtual copies that might stand in for originals after a

fire. But we recognize that, if we

are going to contribute as we claim to the preservation of fragile originals

that are easily damaged by handling, we must supply reproductions that scholars

can depend upon in their research.

Hence our benchmarks produce images accurate enough to be studied at a

level heretofore impossible without access to the originals. As we shall see, in side-by-side

comparisons, images in the Archive are more faithful to the originals in scale,

color, and texture than the best photomechanical (printed) images in all but

the most extraordinary instances, and provide more detail than even unmagnified

originals.

II.

Digital Facsimiles in the Blake Archive

The

Archive’s digital images are scanned from three types of color

transparencies: 35mm slides, 4 x

5-inch, and 8 x 10-inch transparencies. While both of the larger size

transparencies include color bars and gray scales to ensure color fidelity, the

4 x 5 inch transparencies are our preferred and most often used reproductive

source. They are much less expensive to produce and can be scanned directly

instead of through glass (see below). For the sake of consistency, if not also

quality of image, we prefer scanning film to digital images from contributing

collections, where equipment and protocols for digital capture vary. As the

editor responsible for color correcting the digital images, I have verified

most of our transparencies for color accuracy against the original artifact,

and in all cases they have been verified by the photographer employed by the

owner institution. Indeed, for three of the largest collections in the archive,

together consisting of over 1400 images, we brought in our own photographer and

I was the assistant on the shoot. The transparencies were developed at the end

of each day and compared the next morning, before that day’s shoot, to

the originals on a color-corrected

light box. We used Kodak Kodachrome Professional EPP and EPY film, which

captures the soft gradations of watercolors and paper tone, and is the film

type most of our contributing institutions use as well, and we used cool strobe

light to illuminate the originals.

The size of our originals range from 2.5 x 2 inches for the smallest

illuminated prints to over 30 x 20 inches for the largest watercolors

and paintings. These measurements, though, refer to the size of the image

and

not leaf or canvas. For

example, plate 4 of The Book of Urizen copy G is approximately 6 x 4 inches, but was printed on a

sheet 11.5 x 9 inches (illus. 3).

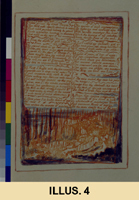

Rather than photographing the full sheet,

we cropped to the image, leaving just enough room on the 4 x 5 inch film

for the color bars and gray scale (illus.

4). Admittedly, cropping discards bibliographical information, such, as

in this case, the plate’s poor registration to the sheet, and thus fails

to represent the artifact itself. Consequently, like print reproductions and

facsimiles, our digital images (illus.

5) also hide poor registrations, but our reasons for cropping are more

technical and pedagogical than economic and aesthetic.

Recording the image on the film as large

as possible reduces the scaling ratio between reproductive source and original,

which ensures greater accuracy in the digital image (see below); cropping out the image’s margins

significantly reduces file size, and, for most images, enables the image to be

shown within the Archive’s interface on monitors 17” or larger

without scrolling. For us, cropping at this initial stage of photography is

determined by the material constraints of the electronic medium—by file

sizes, monitor size, screen resolutions, and band width.

Until May of 1998, we scanned our transparencies at IATH on a Microtek

Scanmaker III, a flatbed scanner with a transparent media adapter. Since

then,

we have scanned them at UNC on a Microtek Scanmaker V, which, instead of

the adapter built into the lid, uses a separate drawer to hold 4 x 5-inch

film

inside the scanner's body, where it is scanned using Microtek's EDIT (Emulsion

Direct Imaging Technology) system. Scanning transparencies directly and

not

through glass creates a sharper scan (one less layer to absorb light), eliminates

Newton rings (interference patterns resulting from the contact of film and

glass), and reduces dust. Slides (which have only rarely been used in the

Archive) are scanned on either a Nikon LS-3510AF Slide Scanner or a Microtek

35t Plus Scanner.

The

baseline standard for all scanned images to date is 24-bit color and a

resolution of 300 dots per inch (dpi). Depending on the size of the original,

the scanned image is scaled against the source dimensions of the original

artifact at 1:1, 1:2/3, or 1:1/2. We have found that these settings produce

excellent enlargements and suitably sized inline images. Nonetheless, we have

begun to scan at 600-dpi now that our hardware (the Macintosh G3 is equipped

with 384 MB of RAM and 9 GB of internal storage and another 5 GB external) can

better accommodate the larger file sizes that result, and we have also changed

the type of image file we color-correct. Initially, we saved our raw 300-dpi

scans as TIFFs and as JPEGs, storing the TIFFs (Tagged Image File Format) on

8mm magnetic Exabyte tape—data which we have since migrated to CD-ROM (in

Mac/ISO 9660 hybrid format). Now, by scanning at 600-dpi, we capture more

information, including paper tone and texture, but the resulting files are

quite large—artifacts a mere 8.5 x 6.5 inches produce files in excess of

100 MB. Consequently, we store these raw scans on CD-ROM as (LZW-compressed)

TIFFs, which cuts the file size in half. From the original 600-dpi TIFF image,

we also derive a 300-dpi (compressed) TIFF, which significantly reduces the

file size with no noticeable loss of information. Even so, like its parent

image, the 300-dpi TIFF is saved on CD-ROM and stored outside the Archive

proper.

The

color-corrected images that we

display to our users in the online Archive are all served using the JPEG (Joint

Photographic Experts Group, ISO/IEC 10918) format. A 300-dpi JPEG is derived as

the final step of the color-correction process and sent by electronic file

transfer from UNC to the Archive’s server at Virginia, where an assistant

logs its arrival on our internal tracking sheets (this 300-dpi JPEG becomes the

“enlargement” we offer

of each image and which on most systems takes a few seconds longer to load for

viewing). The assistant then derives a100-dpi JPEG (which will become the inline image, i.e., the image in our

Object View Page) from the color-corrected 300-dpi JPEG using ImageMagick,

software that enables the batch processing of image files from the UNIX command

line. Users are thus presented with an inline image at 100-dpi, which is fine

enough for most purposes and requires graphics files of modest size that

facilitate downloading and movement from image to image. And they have the

option to view an enlargement at 300-dpi for the study of details.

Scanned

images less than 9.5 x 7 inches—which includes all the illuminated

works—are scaled at 1:1 so the inline image will display at true-size on

a monitor with a 100-dpi screen-resolution. Its enlargement will be

approximately three times the original. Images between 9.5 x 7 and 16 x 12

inches are scaled at 1:1 to produce enlargements three times the original, but

the inline images are resized manually so that they can be viewed in their

entirety without scrolling; users wishing to see it at true size can increase

its size manually till it matches the measurements of the original, which are

given under the image. Images larger than 16 x 12 inches are scaled at 1:2/3 to

produce enlargements two times the size of the original, and images larger than

24 x 30 inches are scaled at 1:1/2 to produce enlargements one and a half times

the original, and the inline images in both categories are resized manually.

Though only two times or less the originals, on screen these enlargements

provide enormous amounts of detail.

As

part of the scanning process for each image, a project assistant completes a

form known as an Image Production (IP) record. The IP records contain detailed

technical data about the creation of the digital file for each image, including

owner institution, film stock, type, generation, and date made, measurements of

original image, reproductive source, and output, the scaling ratio, file size,

and scanner hardware and software. These records, retained in hard copy at the

project’s office, become part of the Image Information record that is

inserted into each image as metadata . Each and every image in the Archive also

contains textual metadata comprising its Image Information record (see below).

The

300-dpi (compressed) TIFF images generated by the scans are each individually

color-corrected against the original transparency or slide while it is on a

color-corrected light box (the

same one used in the photo shoots sponsored by the Archive). As noted, the

fidelity of the transparencies can be trusted, having themselves been verified

for color accuracy against the original artifacts. We correct the image using

Adobe Photoshop and calibrated, hooded Radius PressView 17SR and 21SR monitors.

We now color-correct the TIFF instead of JPEG because the lossless compression

does not discard image data each time changes are made to the file in

Photoshop. This 300-dpi (compressed) color-corrected TIFF is then saved on

CD-ROM. The color-correction process, which takes upwards of thirty

minutes—and sometimes as long as several hours—for each of the

Archive’s 3000 images is necessary to bring the color channels of the

digital image into alignment with the hues and color tones of the original

artifact. This is a key step in establishing the scholarly integrity of the

Archive because, although we cannot control the color settings on an individual

user’s monitor, the color-correction process ensures that each image will

match the original artifact when displayed under optimal conditions (which we

specify to users).

Images need to be “color- corrected” because the very

process by which they are digitized results in a loss of color quality.

Color correcting

compensates for this loss by changing an image’s shadows, midtones,

and /or highlights, hue, and saturation so that the colors of the final

output,

whether print or screen, conforms to the original—or original idea

of the graphic artist. Color correcting images is a form of editing, and

as such

is work requiring decisions best made by an editor and not scanning assistants.

Our aim is accuracy, to make reproductions appear as close as possible to

what they reproduce, but the means of doing so may seem overly subjective,

of requiring too much human intervention. To assume that machines—camera

and scanner—yield more objective results of and by themselves, however,

is mistaken. At the very least, the color cast created by the scanning

process

(true of even high-end drum scanners used by fine-art printers) must be removed

and the image sharpened with “unsharp mask.” [10] Most likely it will need more work, though

only a handful of Photoshop’s numerous features, such as curves,

levels, unsharp mask, color balance, and hue and saturation, will be

employed. But

one also needs to master the temptation to “improve” the original

aesthetically—eliminate foxing and other blemishes, for example, or

increase or decrease the saturation of certain colors—“restore”

it—bring a two hundred year old faded wash drawing to its presumed

original pristine condition. While absolute accuracy is not possible—not even

for Photoshop—the electronic medium combined with the skills and good

eyes of an editor can create trustworthy reproductions.

But

good eyes and skill in Photoshop will be for naught if the quality of the

reproductive source is compromised. As noted, we prefer to use 4 x 5 inch

transparencies instead of 35mm slides, in part because the former comes with color

bars and gray scales, has a smaller scaling ratio, and is what photographers

working for museums and libraries routinely provide for color reproductions.

Slides, on the other hand, while technically transparencies, are not meant for

publication. Indeed, all the institutions we deal with prohibit their

reproduction and make them for study, or, more exactly, reference purposes

only. A similar situation between high fidelity and reference exist in digital

reproduction. Many images of art

works on the Web today are from slides scanned at 72-dpi; these can give a

sense of composition or design, but cannot be used for scholarly and editorial

work, no more than Dover reproductions can (see below). Images from slides, even when scanned

at very high resolutions—which results in files of enormous

size—cannot match the quality of images scanned from transparencies

because they have a far lesser amount of photonic data.

A comparison between a transparency and a slide, both scanned at 300-dpi,

scaled at 1:1 to the original, and shown at 100%, the size of our enlargements,

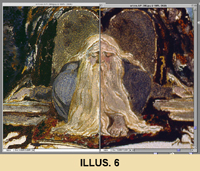

is most revealing. In a bit of “fearful symmetry,” the title plate

to Blake’s The Book of Urizen copy C is here reconstructed

with a left side from a transparency and a right from a slide (illus.

6). The transparency captures the texture of the paint and subtle gradations,

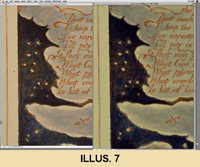

missing in the slide. The two versions of Blake’s America, a Prophecy

copy O plate 13 are even more telling, because here transparency (left) and

slide (right) are uncorrected raw scans. The transparency comes in sharper

and with more information, requiring less manipulation than the slide (illus.

7).

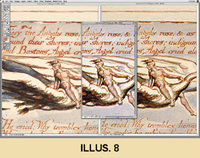

The difference between the two remains

as pronounced after they have been color corrected and sharpened (illus.

8), though both are far superior to the middle image, which is from

a slide scanned at 72-dpi but enlarged 400% to provide detail analogous

to the

two 300-dpi scans. Unlike them, however, it badly pixelates at this size

and distorts its information. [11]

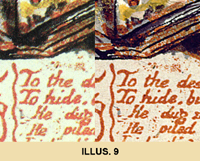

Trying to coax detail out of a 72-dpi scan is like using a magnifying

glass to examine a photomechanical reproduction, which, in place of pixels,

yields the interfering dots of the photographic screen (illus.

9).

Unless one examined originals with slide

loops (small but powerful magnifying glasses for 35mm slides placed directly

on the artifact and thus unacceptable to curators and librarians) or conventional

magnifying glasses, one had no choice but to resort to reproductions and facsimiles

for detail. The original Blake Trust facsimiles, produced through a combination

of collotype and hand-painting through stencils, have no screen, but, when

magnified, do reveal visual "boundaries" between colors (the result

of using stencils). Indeed, the Archive’s images have achieved greater

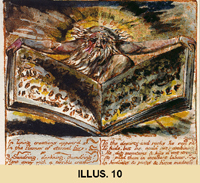

color fidelity in some notable instances—for example, several plates

in the Blake Trust's facsimile of The Book of Urizen, copy G (left) have a reddish hue not found

in the originals. In this respect, the images in the Archive (right) are truer

to the tonality of the originals (illus.

10).

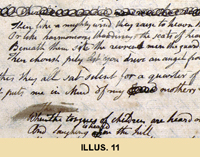

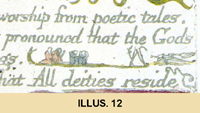

Our 300-dpi (JPEG) enlargement yields superb detail for close inspection

of printing and coloring, enabling one to study paint layers, differentiate

what was printed from plates and what added to impressions, examine emendations

in manuscripts (illus.11)

and the tiny hieroglyphic like figures and decorations between lines of text

(illus. 12).

They provide the raw data for editing, enabling

one to compare multiple versions of texts and take on those most puzzling

of all marks, the ones simultaneously part of the text and design. For example,

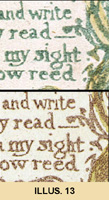

in plate 4 (lines 13-16) of Songs of Innocence and of Experience (illus.

13), is the mark after “write” punctuation (comma or

fat period) or tendril—or both?

|

After “sight” and “reed,”

Erdman records a colon and a period, though the latter is more oblong than

the former. In copy F (top), Blake colored the tendril yellow but left the

tip green in the shape of a period, forming a colon after the fact. A happy

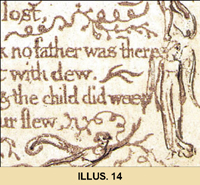

accident? More challenging are

designs  like that of plate 13 of Songs (illus.14)

which force one to ask if figures or parts of them can function as stops,

whether non-linguistic marks belong to the linguistic code.

like that of plate 13 of Songs (illus.14)

which force one to ask if figures or parts of them can function as stops,

whether non-linguistic marks belong to the linguistic code.

Enlargements of good digital images can yield more information than

the originals, as can enhancements, which can reveal such subtleties as

a

black-inked signature faded into a black wash, or, when creatively “deformed,”

as demonstrated by Jerome McGann, yield hidden structural information. [12] Often as important as enlargement is

comparison; in the Archive one can, with almost all the illuminated books,

immediately

check an image in one copy against other copies of that book, which has never

been possible with the printed record and rarely in any one real collection.

Reproducing

images more accurately than print, images not in print, and multiple copies of

images, makes the Archive the first place to stop when studying Blake. The

Archive’s scholarly integrity, however, also requires that its images be

true size, because scale

can be a significant aspect of the experience and meaning of an object. We grant structural priority to the

physical object by accounting archivally and editorially for the original size

of Blake's works, whether plates, paintings, drawings, manuscripts, or printed

pages. We have done that in two

ways, by displaying the actual size of every object directly beneath it, and by

providing ImageSizer, a sophisticated image manipulation tool, available from

every Object-View Page. A new Java applet developed at IATH with the Blake

project in mind, ImageSizer can resize images on the fly at the size of

originals on monitors whatever their resolution. It is this feature in the

Archive that makes our images digital “facsimiles.”

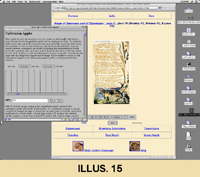

ImageSizer’s principle function for the Archive is to allow users

to view Blake’s work on their computer screens at its actual physical

dimensions. Users may invoke the ImageSizer’s calibration applet to

set a “cookie” informing the ImageSizer of their own unique screen-resolution

(illus. 15).

actual physical

dimensions. Users may invoke the ImageSizer’s calibration applet to

set a “cookie” informing the ImageSizer of their own unique screen-resolution

(illus. 15).

Users hold an actual ruler up against the one on the screen

and use the slider bar to align the measurements of both. Screen resolution

thus determined, the applet automatically resizes the images (which have already

been scaled to display at true size on a 100-dpi screen) to appear at true

size on the user’s monitor. Based on this data (recorded in the cookie),

all subsequently viewed images will be resized on the fly so as to appear

at their true size on the user’s screen. If a user returns to the Archive

at some later date from the same machine (and the resolution has not been

changed), the data stored by the cookie will remain intact, and there will

be no need to recalibrate. Users may also set the ImageSizer’s calibration

applet to deliver images sized at consistent proportions other than true size,

for example, at twice normal size (for the study of details).  In addition,

the ImageSizer allows users to enlarge or reduce the image within its on-screen

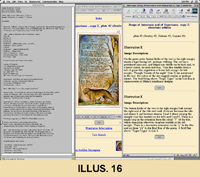

display area, and to view the textual metadata comprising the Image Information record

embedded in each digital image file (illus.

16).

In addition,

the ImageSizer allows users to enlarge or reduce the image within its on-screen

display area, and to view the textual metadata comprising the Image Information record

embedded in each digital image file (illus.

16).

The

Image Information record combines the technical data collected during the

scanning process from the Image Production record with additional bibliographic

documentation of the image, as well as information pertaining to provenance,

present location, and the contact information for the owning institution. These textual records are, at the most

literal level, a part of the Archive's image files. Image files are typically considered to be nothing but

information about the images themselves (the composition of their pixelated

bitmaps, essentially); but in practice, an image file can be the container for

several different kinds of information. The Blake Archive takes advantage of this

by slotting its Image Information records into that portion of the image file

reserved for textual metadata.

Because the textual content of the Image Information record now becomes

a part of the image file itself in such an intimate way, this has the great

advantage of allowing the record to travel with the image, even if it is

downloaded and detached from the Archive's infrastructure. The Image Information record may be

viewed using either the “Info” button located on the control panel

of the Archive’s ImageSizer applet or with the Text Display feature of

standard software such as Adobe Photoshop or X-View.

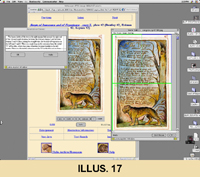

Also from the Object View Page, a user can evoke Inote, the Archive’s

other Java applet. Inote is an image-annotation tool which permits us to

append textual notes (“annotations”) to selected regions (or “details”)

of a particular image; these annotations are generated directly from the

SGML-encoded

illustration descriptions prepared by the editors. Inote functions most powerfully

when used in conjunction with the Archive’s image searching capabilities,

where it can open an image found by the

search engine, zoomed to the quadrant of the image containing the object(s)

of the search query, with the relevant

textual annotation displayed in a separate window (illus.

17). From there, Inote allows the user to enlarge the image for further

study and/or to access additional annotations located in other regions of

the image. Inote may also be invoked directly from any of the Archive’s

Object View pages, allowing users to “browse” the annotations

created for a given image.

textual notes (“annotations”) to selected regions (or “details”)

of a particular image; these annotations are generated directly from the

SGML-encoded

illustration descriptions prepared by the editors. Inote functions most powerfully

when used in conjunction with the Archive’s image searching capabilities,

where it can open an image found by the

search engine, zoomed to the quadrant of the image containing the object(s)

of the search query, with the relevant

textual annotation displayed in a separate window (illus.

17). From there, Inote allows the user to enlarge the image for further

study and/or to access additional annotations located in other regions of

the image. Inote may also be invoked directly from any of the Archive’s

Object View pages, allowing users to “browse” the annotations

created for a given image.

III.

Conclusion

Blake’s

illuminated works are widely dispersed and more and more severely restricted as

a result of their value, rarity, and fragility. Studying them, at both the

introductory and advanced levels, requires accurate reproductions of as many

copies of each book as is possible. One might wish to argue that translating

Blake’s analogue hand into the discreet digits of types for the purpose

of publication merely recreates the relation between manuscript (fair copy) and

letterpress, and hence appropriate for texts from the period. Such an argument,

though, would not only ignore Blake’s intentions, but it would also

dismiss as meaningless the historical, technical, and aesthetic information

provided by the poem’s form. Though not reproducible in the digital

technology of his day, and unevenly so by the dots per inch that followed,

Blake’s pictorial poetry can be accurately reproduced in today’s

digital technology when imaging protocols such as those outlined here are

followed. For most scholarly purposes, the resulting reproductions will more

than suffice, or, at the very least, adequately prepare one for examining

originals, those not reproduced in the Archive and those for which bibliographic

information necessarily requires handling the artifact.

The

Archive’s exceptionally high standards of site construction, digital

reproduction, and electronic editing have made possible reproductions that are

more accurate in color, detail, and scale than the finest commercially

published reproductions and facsimiles, and texts that are more faithful to

Blake’s own than any collected edition has provided. We have applied equally high standards

in supplying a wealth of contextual information, which includes full and

accurate bibliographical details and meticulous descriptions of the content of

each image. Finally, users of the

Archive can attain a new degree of access to these works through the combination

of powerful text-searching and (for the first time in any medium) advanced

image-searching tools that are made possible by the editors’ detailed

image descriptions and innovative software.

We

are hoping, of course, that the Archive, once extended to encompass the full

range of Blake’s work, will ultimately set a new standard of

accessibility to a vast collection of visual and textual materials that are

central to an adequate grasp of the art and literature of the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries. But we have

also come to see the Blake project as a pacesetting instance of a fundamental

shift in the ideas of “archive,” “catalogue,” and

“edition” as both processes and products. Though

"edition" and "archive" are the terms we have fallen back

on, in fact we have envisioned a unique resource unlike any other currently

available—a hybrid all-in-one edition, catalogue, database, and set of

scholarly tools capable of taking full advantage of the opportunities offered

by new information technology.

1. “The Tyger,” Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy C.

2. “The Tyger,” Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy Z.

3. The Book of Urizen copy G, plate 4, full sheet.

4. The Book of Urizen copy G, plate 4, uncorrected transparency with color bars and gray scale.

5. The Book of Urizen copy G, plate 4, corrected in Archive’s Object-View Page.

6. The First Book of Urizen copy C, title plate,reconstructed from transparency (left) and slide (right) scanned at 300-dpi, detail.

7. America, a Prophecy copy O plate 13, uncorrected transparency (left) and slide (right) scanned at 300-dpi, detail.

8. America, a Prophecy copy O plate 13, uncorrected transparency (left) and slide (right) scanned at 300-dpi, with image from slide scanned at 72-dpi (middle), detail.

9. The Book of Urizen copy G, plate 5, photographic screen of Dover Publication reproduction (left) and Archive digital image (right), detail.

10. The Book of Urizen copy G, plate 5, collotype and stencilled coloring of Blake Trust Facsimile (left) and Archive digital image (right), detail.

11. Island in the Moon manuscript, page 14 , detail.

12. Marriage of Heaven and Hell copy D, plate 11, hieroglyphic-like figures between lines 13 and 15, detail.

13. Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies C (bottom) and F (top), plate 4, lines 13-16, detail.

14. Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy C, plate 13, lines 5-8, detail.

15. ImageSizer’s calibration applet setting a “cookie” informing the ImageSizer of user’s own unique screen-resolution.

16. Textual metadata comprising the Image Information record embedded in each digital image file.

17. Inote used in conjunction with the Archive’s image searching capabilities, where it can open an image found by the search engine, zoomed to the quadrant of the image containing the object(s) of the search query, with the relevant textual annotation displayed in a separate window.