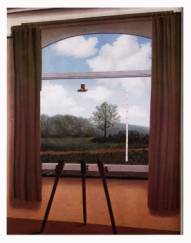

Representation: La Condition Magritte

Oil paint and oil stick on paper, 90 x 42 inches

Representation: La Condition Magritte

Oil paint and oil stick on paper, 90 x 42 inches

An alternate title for this painting is Turtles All the Way Down. It refers

to the Iroquois creation myth in which North America lies on the back of a

giant sea turtle. And what lies under that turtle? Another turtle. And so on.

To me this describes the complexity of representation, a subject dear to the

hearts of both artists and humanists, more poetically than the now fashionable “simulacrum.”

The Magritte painting I am alluding to is La Condition Humaine. In it Magritte plays with the ideas of painting as a window on reality and a mirror reflecting or imitating that reality, ideas that began with the introduction of perspective during the Renaissance. He pictures the tension between reality and illusionistic representation. He plays also with the idea of perception, by showing a tree as both inside and outside the room simultaneously. “This is how we see the world,” Magritte said, “we see it outside ourselves and at the same time we only have a representation of it in ourselves.” He executed at least four versions of this painting, all with the same title; the one reproduced here is the first, from 1934. And he executed many more paintings with the same structure and themes, which is why I so closely associate the condition of pictorial representation with Magritte.

I sought to bring him into my painting conceptually but not stylistically.

Magritte’s “world” outside the window, whether seen as mirrored

in or projected from canvas, is depicted realistically, as the model that art

reproduces, implying a real space that we know is spatial illusion or representation.

I too wanted to exemplify representation by showing a painting within a painting

and a painting of a painting, but wanted to be more explicit about there being

nothing beyond the canvas, that it is all, so to speak, “canvas all the

way down.” Consequently, in Representation there is no interior or exterior;

the objects in the model and its reproduction share the same space and the

same artificial codes and material means of representation that make them simultaneously

abstract and representational, simultaneously two and three dimensional. The

objects float in color yet feel grounded in space, on a table or surface implied

but not represented. The absence of color gradation creates their flatness,

the rules of perspective create their sense of depth, and the breaking of these

rules where model and reproduction overlap reinforce the play and artificiality

of the codes. At that intersection is also an aesthetic conundrum, a one-to-one

mapping of model and image that defies originality and defines forgery and

yet raises the concept of the exact repeatable image that defines Print, which

has been, since its invention in the Renaissance, responsible for the rapid

advancement and expansion of the arts, humanities, and sciences. The objects

in the “original” and “copy” are mostly circles whose

colors represent specific fruits and vegetables, are signs with specific referents,

but delineated in a manner meant to reiterate the struggle between line and

color, which in the history of western art encapsulates the debate between

Classicism and Romanticism. I see the bounding line of the classically trained

William Blake and its dissolution into color so characteristic of Turner (whose

name is on the wine bottle), and see also in the wiry black lines and unfinished

reproduction on the easel the image of ideas coming into being. And that is

what excites me most about The Institute for the Arts and Humanities, that

it is a place where ideas are born, shaped, developed, and shared.

I sought to bring him into my painting conceptually but not stylistically.

Magritte’s “world” outside the window, whether seen as mirrored

in or projected from canvas, is depicted realistically, as the model that art

reproduces, implying a real space that we know is spatial illusion or representation.

I too wanted to exemplify representation by showing a painting within a painting

and a painting of a painting, but wanted to be more explicit about there being

nothing beyond the canvas, that it is all, so to speak, “canvas all the

way down.” Consequently, in Representation there is no interior or exterior;

the objects in the model and its reproduction share the same space and the

same artificial codes and material means of representation that make them simultaneously

abstract and representational, simultaneously two and three dimensional. The

objects float in color yet feel grounded in space, on a table or surface implied

but not represented. The absence of color gradation creates their flatness,

the rules of perspective create their sense of depth, and the breaking of these

rules where model and reproduction overlap reinforce the play and artificiality

of the codes. At that intersection is also an aesthetic conundrum, a one-to-one

mapping of model and image that defies originality and defines forgery and

yet raises the concept of the exact repeatable image that defines Print, which

has been, since its invention in the Renaissance, responsible for the rapid

advancement and expansion of the arts, humanities, and sciences. The objects

in the “original” and “copy” are mostly circles whose

colors represent specific fruits and vegetables, are signs with specific referents,

but delineated in a manner meant to reiterate the struggle between line and

color, which in the history of western art encapsulates the debate between

Classicism and Romanticism. I see the bounding line of the classically trained

William Blake and its dissolution into color so characteristic of Turner (whose

name is on the wine bottle), and see also in the wiry black lines and unfinished

reproduction on the easel the image of ideas coming into being. And that is

what excites me most about The Institute for the Arts and Humanities, that

it is a place where ideas are born, shaped, developed, and shared.

Joseph Viscomi